David Lynch in Los Angeles, August 2014. PIC: Just Loomis

“I wanna have a good day today.” — David Lynch, ‘Good Day Today’.

There is a playfulness to David Lynch. The director has a sense of humour that can easily be missed. But it is there: in the scenes featuring Billy Ray Cyrus in Mulholland Dr, in the kid incongruously dance-shuffling past a school hallway in the pilot to Twin Peaks. And it was on full, glorious display in the mischievous smile that kept creeping over Lynch’s face during a Question and Answer session in Brisbane recently.

Incongruously conducted by David Stratton (is Lynch not more of a Margaret person?) the session coincided with the launch of Between Two Worlds, a retrospective-of-sorts now showing at the Queensland Gallery of Modern Art.

Devoted to Lynch’s complete oeuvre: his paintings, sketches, sculptures, sound and films, the exhibition makes you look hard to find the playfulness. Piece after exhibited piece, it is the darkness that proliferates.

How to even begin approaching David Lynch through the written word? For more than 40 years he has deployed moving and stationery images, sound and sculpture to explore that which cannot be expressed through language alone. As exhibition Curator José Da Silva says, Lynch’s work explores the movements “between the interior and exterior spaces of the body, and the physical and psychic worlds the body occupies”. In this, the exhibition has the upper hand over the review: it is experiential.

Between Two Worlds begins with a sketch of a room Lynch drew in 1977, followed by a three-dimensional version constructed 30 years later. As you walk through this room you are quite literally traversing a physical manifestation of Lynch’s unconscious.

If you look back after walking through, you see the room is nothing more than some painted scaffolding. As the singer in Club Silencio says in Mulholland Dr, “No hay bando (there is no band). It is an illusion.”

Unsettling? Perhaps. But this is a classic Lynch theme, and there is some comfort in its repetition.

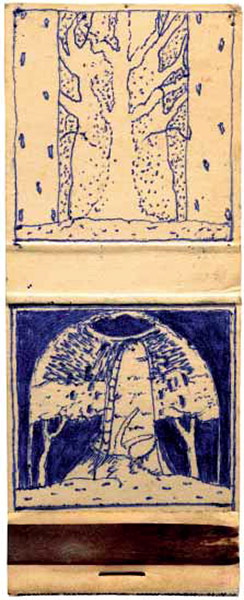

Soon after this room are a series of micro-sketches on napkins and matchboxes. Their dark intricacies disturb on two levels. Firstly, there is the subject matter: windswept, cold and wet vistas are depicted, some of which are seen through frames. The addition of these frames suggests a “safe space” impervious to the harshness depicted on the other side. Yet it also suggests a subject who is not the viewer. Whose frame is this?

Secondly, there is the medium. Napkins and matchboxes: coffee and cigarettes. Pure Lynch. But frighteningly so, for they suggest the surreal horrors of his unconscious have been birthed onto the banal props of everyday life. These images are not safely projected onto distant film screens, they are bursting through the everyday, through napkins and matchboxes.

The darkness might proliferate, but it does not completely dominate this exhibition. Cleverly, Between Two Worlds ends with a sustained, and necessary, focus on Lynch’s music, as well as his various online endeavours.

The fine line between horror and comedy is absurdly erased in the repetitive video clip for his song Crazy Clown Time, which features teenage stereotypes interacting in surreal ways. Glimpsed throughout is the face of David Lynch, wearing tacky sunglasses, repeating the words “it was a crazy clown time” again and again. It’s ridiculous, kind of hypnotic, and very funny.

So too is DumbLand, a crudely drawn series of comically violent short animated films that are ultimately kind of sad. The series, about a family of slobs in the American suburbs, is The Simpsons through the looking glass. In one episode, a doctor keeps asking the father of the family if “it hurts” while hitting and stabbing him in increasingly violent ways. “No,” the man replies again and again, before finally reaching his breaking point and violently strangling the doctor. Fin.

What exactly is the point? What is the point of any of this? The answers are unknowable, irrational. Don’t bother asking Lynch for clues to understanding his work. As David Stratton found out the hard way, he is loath to discuss meaning. “As soon as you put things into words,” he has lamented, “no one ever sees (the art) the same way.”

There is an overriding sense at the end of this exhibition that a well of meaning lies just beyond reach. You can sort of work your way towards it but in the end you are doomed to be always and forever just on the cusp of reaching it. This is not, necessarily, a criticism. It is the very point of Between Two Worlds.

This sense of ambivalence, this sense that maybe things are going on here that we can’t rationalise, is perhaps best demonstrated by way of example.

“We live in a dream,” said Lynch. “One day each of us wakes up and realises.”

“That’s a very Lynchian thing to say,” replied Stratton.

“Well no, it’s the truth.”

► David Lynch: Between Two Worldsruns at Queensland’s Gallery of Modern Art until June 7, 2015.