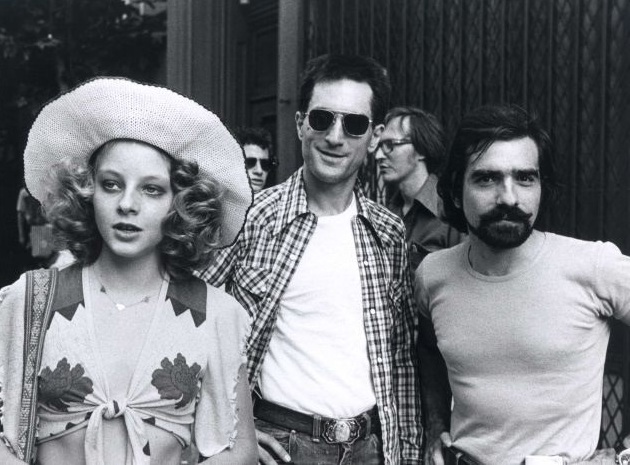

‘Scorsese’ blends “a curated hagiography and a very smart exploration of Marty’s chief preoccupations.” PIC: Alexandra Glen / Featureflash

The Scorsese exhibition is just the latest example of our major cultural institutions’ obsession with mammoth winter exhibitions.

The Australian Centre for the Moving Image bills this as a major opportunity to “explore the world” of the director, whose career now spans five decades.

It’s justifiably easy to be cynical about these types of exhibitions — a big name draws a crowd, which brings money, but beyond bodies walking through the door and exiting through the gift shop, is there a point to the whole thing?

Thankfully, Scorsese rather skillfully manages to be both a curated hagiography and a very smart exploration of Marty’s chief preoccupations.

It’s justifiably easy to be cynical about these types of exhibitions — a big name draws a crowd, which brings money, but beyond bodies walking through the door and exiting through the gift shop, is there a point to the whole thing?

Dimly lit and punctuated by pools of red light, the exhibition is divided into nine distinct zones. They cover the biographic (‘Family’), thematic (‘Lonely Heroes’, ‘Men & Women’, ‘New York’) and technical (‘Editing’, ‘Cinematography’).

Littered throughout are the key selling points for these types of exhibition: the objects that accumulate around the filmmaking process. We’re presented with Daniel Day Lewis’s costumes from Gangs of New York, including a tiny American eagle contact lens he wore. Elsewhere, letters between Scorsese and Jean-Luc Godard, location-scouting memos for The Wolf of Wall Street and even a Palme D’Or trophy from Cannes make an appearance.

Influences abound in Scorsese, which is not afraid to veer into showcasing objects, posters and images from other filmmakers. In particular, the exhibition highlights Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s 1948 film The Red Shoes.

This is a movie whose influence is hard to understate. An entire generation of establishment Hollywood filmmakers – Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg and, of course, Scorsese himself – cite it as creative inspiration. It’s a weirdly moving experience to see the titular shoes, now fading, under glass.

It’s an odd thing to look at these costumes in real life. As ACMI’s 2013 exhibition Hollywood Costume demonstrated, without the benefit of direction and a silver screen the dresses aren’t quite as shiny, and the suits are slightly duller, than you remember them.

There are many screens littered around Scorsese to remind us of this disconnect, and therefore Scorsese’s skill as a director.

He was appointed to the Hollywood pantheon so long ago that it’s easy to forget just how great a filmmaker Scorsese is. He’s so good that I found myself marveling at clips for reasons that were entirely different to why they were included in this exhibition.

Take a scene from The Departed, selected to demonstrate how Scorsese directs men and women interacting.

Police officer Billy (Leonardo DiCaprio) enters the house of psychiatrist Madolyn (Vera Farmiga). They have a conversation, and a soft whistle comes over the soundtrack, growing ever louder until the scene cuts to her kitchen. The conversation continues, but now they have mugs in their hands.

It’s so simple but it enlivens what could otherwise very easily be dully shot dialogue. It’s a particularly admirable attention to detail that helps lift his films above the banal serviceability of so much American filmmaking.

The subject matter helps, too. Scorsese does a very good job of exploring the themes that preoccupy the filmmaker.

New York City is the obvious contender here. This section of the exhibition rather cleverly contains a giant map of Manhattan, spotlighting various filming locations and showing us the relevant clips.

Martin Ansin’s fabulous poster for a retrospective screening of Taxi Driver also makes an appearance. It somehow manages to distill the entire film’s unfolding vision of night-time New York into one panel.

But the highlight of this section, and indeed the whole exhibition, is a series of wonderfully intimate photographs Scorsese took of his neighbourhood, New York City’s Little Italy, in the 1960s. It’s hard not to see these images as the unassuming foundation upon which a half-century of celebrated moviemaking was built.

Still, there are a few issues with Scorsese, mostly relating to its form as a physical exhibition.

A common problem for exhibitions such as this is sound management. Taxi Driver’s soundtrack is utterly distinctive, a masterpiece of film scoring even, but annoyingly it repeats loudly under a clip playing almost smack bang in the middle of the exhibition. The noise carries through the hall.

If a blockbuster, bums-on-seats model is increasingly driving what we get to see, then admittedly we could do a lot worse than this . . . Scorsese manages to explore some fascinating issues in an intelligent, accessible way. I wonder how long our luck will last.

Attempts at breaking away from the wall and screen and into three-dimensional gallery space come across as mostly gimmicky. At the exhibition’s beginning there’s a pointless, cheap-looking recreation of Scorsese’s apartment, around which are situated screens showing clips of his parents.

At the other end of the exhibition, a white boxing ring has been set up to watch clips from Raging Bull.

These elements do nothing except make it feel as if the curators are clasping at justifications for making this an exhibition. There’s no need – the material and its organisation speaks more than ably for itself.

Scorsese comes at an interesting time for ACMI. The centre recently launched ACMI X, a co-working space in Southbank. Its stated aim is to “foster creativity and collaboration, experimentation and inspiration.” Desks are $600 a month.

So why is a cultural institution establishing offices for the “creative industries”? Probably for the same reason they’ve established a philanthropic “Partnerships” program.

Probably for the same reason that Scorsese is currently showing.

Money for the arts is hard to come by these days.

If a blockbuster, bums-on-seats model is increasingly driving what we get to see, then admittedly we could do a lot worse than this. The NGV’s recent Andy Warhol/Ai Wei-Wei exhibition comes to mind.

Scorsese manages to explore some fascinating issues in an intelligent, accessible way. I wonder how long our luck will last.

► Scorsese is at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image until September 18.