Anna Axiak says she cannot breathe normally without prevention and relief medication. The Kealba resident’s symptoms came as a shock – she had never been an asthma sufferer. Until, she says, the smell.

At first glance, Kealba, in Melbourne’s north-west, looks little different from other post-war suburbs: brick houses with well-tended gardens. Except it’s right beside a landfill site that’s burning – and has been for years.

The breeze blows the odour from the blaze towards the houses. Residents describe the smell as a mix of chemical fertiliser, rotten eggs, molten chemicals and plastics, and animal carcasses.

“It consumes your life,” says resident Nicole Power. “You just can’t escape.”

The hotspots have been burning for more than three years. The landfill, which accepts “solid inert waste”, typically from commercial, industrial, building and demolition activities, is only 60 metres from homes.

The landfill owner-operator is a private company overseen by the second generation of family members. The Barro Group, along with the Environment Protection Authority (EPA), insist the odour does not pose any permanent health risk. But residents believe it is responsible for chronic physical and mental health conditions that have plagued them since the fires started burning.

Residents are frustrated at what they describe as weak and delayed action by the EPA. Last week, the authority cancelled Barro’s licence to operate the landfill after issuing multiple regulatory notices to extinguish the fires and contain the odour. However, it acknowledged the hotspot would continue to burn for up to 18 months after the company disclosed its depth contradicted previous advice.

Meanwhile, since the fires started burning, siblings Raymond and Rhonda Barro have seen their wealth rise to $1.8 billion on the AFR Rich List in 2022, up from $1.65 billion in 2019.

Residents first reported an unusual odour to the EPA in October 2019. The smell intensified, and in November, the Barro Group notified the EPA of four hotspots in two “cells”, as the disposal pits for hazardous waste are called.

The EPA says the hotspots were likely due to “oxygen entering the landfill, and combusting with old, decomposed waste”, and committed to investigate further once all hotspots were remediated.

The Barro Group commenced its remediation work in July 2020. By late 2021, three of the hotspots were extinguished. The largest is still burning.

More than 10,000 odour and health complaints have been made since the hotspots were first detected, according to the Kealba Landfill Odour Report, released by the EPA in July 2022. The odour primarily impacts those living west of the landfill in Kealba and St Albans. They experience increased asthma symptoms, coughing and nausea, among other ill effects, according to the report.

Resident Marian Pham says she too first developed asthma a year after the fires started burning. Pham says she now uses a steroid inhaler to get it under control.

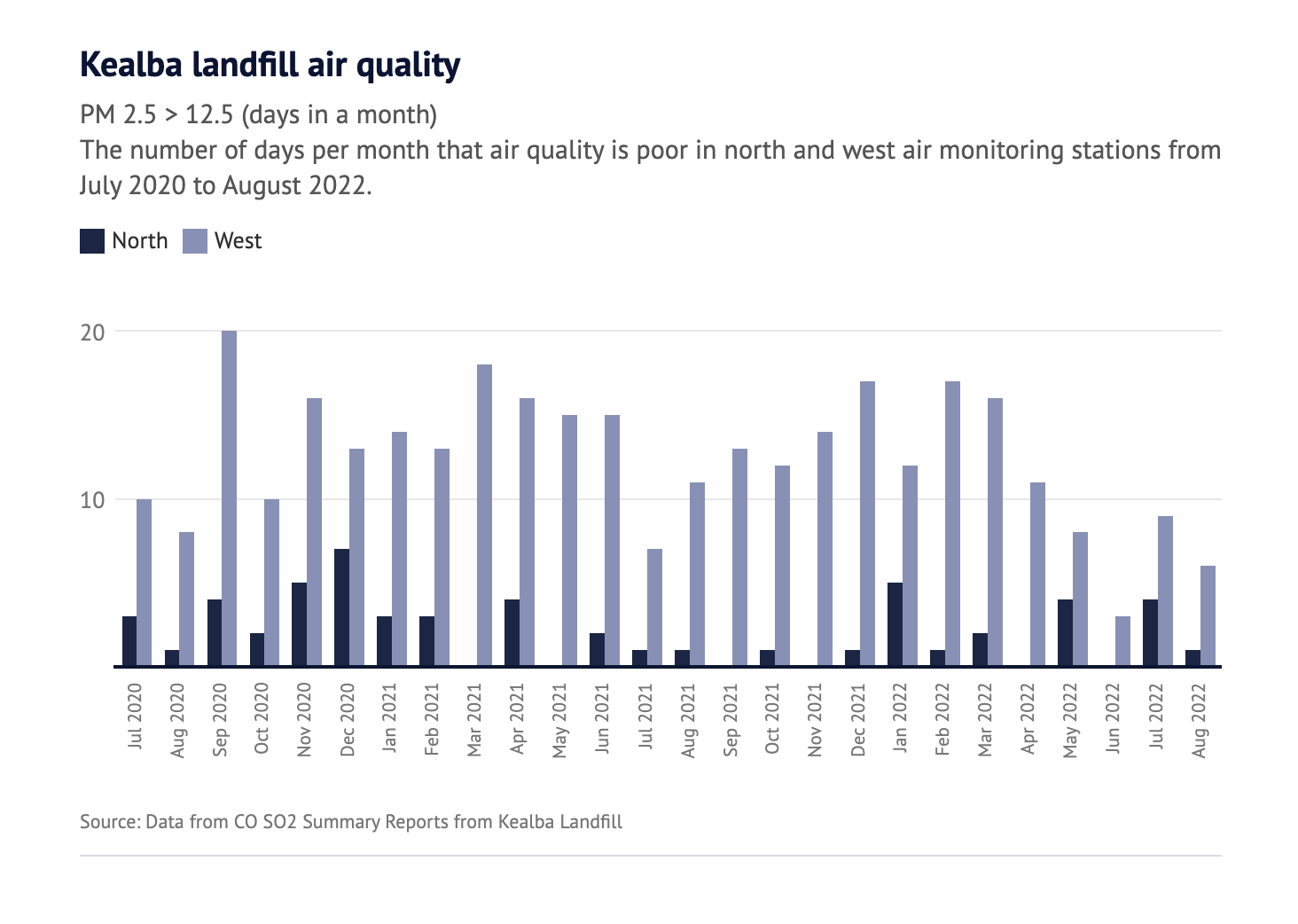

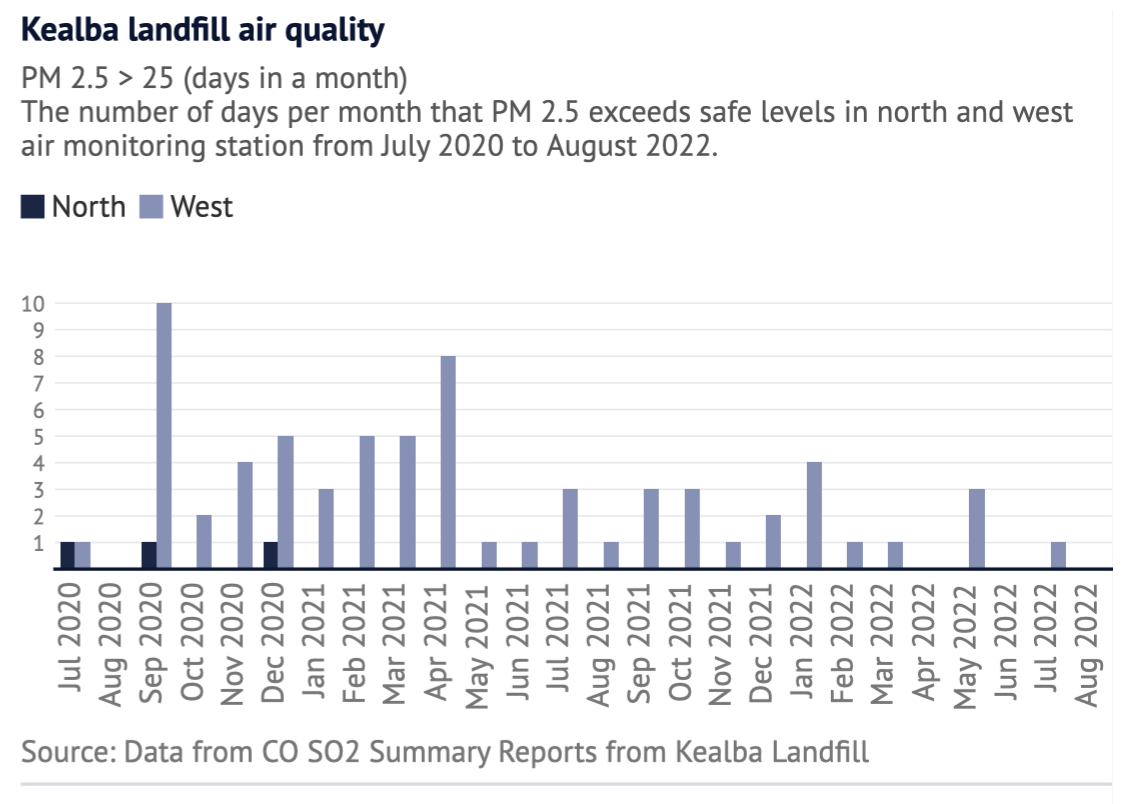

The Barro Group is required by the EPA to conduct monthly air monitoring for key substances at the site, including volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and fine particulate matter known as PM2.5 (tiny airborne pollutants that can travel deep into the lungs).

Barro Group’s monthly reports from its western monitoring station, directly opposite residents’ houses, showed PM2.5 readings exceeded safe levels on nearly thirteen days per month from July 2020 to August 2022. It was poor on close to three days per month.

When Power, who lives 350 metres from the landfill, expressed concern about the unsafe PM2.5 levels, she says the EPA told her they could be caused by traffic rather than the fires.

Power is not convinced. She points out the roads were quiet during the COVID lockdowns. “If it’s from the road, [the unsafe levels] would be at the same time every single day, but [they are] not,” she says.

Then there is the terrible odour itself.

Odours are detected when the “odorant” compounds of airborne chemicals stimulate the olfactory nerve. Cells in the lining behind the nose and in the throat react to these chemical aromas, which can then release inflammatory chemicals that may, in turn, trigger physical symptoms.

According to the US Public Health Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, the human olfactory system can detect chemicals below the threshold levels at which concentrations cause toxic effects in humans. Health symptoms such as asthma can occur from “sub-irritant” odours, with the degree of unpleasantness and an individual’s exposure history believed to play a role.

According to the EPA and the Barro Group, air monitoring results demonstrate odour, while offensive, pose “no issues of concern for long-term community health … in most cases”.

The EPA’s advice on whether odour alone can cause physical ailments is inconsistent. In its 2021 report into the Kealba landfill fires, it describes odours as “concentrations of substances in the air … that stimulate the sense of smell but are below levels at which they would create a physiological response in humans”.

Yet in advice to doctors treating communities near the Kealba fires, the EPA states: “Odours can stimulate the central nervous system causing short-term, reversible physiological effects including triggering of asthma symptoms. Nonetheless, the long-term risk to health from odour exposure is very low.”

Trevor Thornton, environmental consultant at Deakin University and a former EPA employee, says odours without chemicals at harmful levels can still cause distress.

“You can have odour which doesn’t actually necessarily have any really harmful chemicals in it, but it can still make people feel ill,” he says. “[It] can interfere with sleep … and just being outside and enjoying where you live.”

Thornton’s analysis is consistent with a 2009 paper, published in the American Journal of Human Health, which found people exposed to persistent foul odour from pig farms avoided engaging in outdoor activities and socialising, and experienced sleep disruption – all essential for good health – and appeared to trigger “stress and negative mood”.

Local Jamie Ramsay says the psychological impact of living with the odour was especially challenging during COVID-19 lockdowns.

“Not to be able to escape [it was] detrimental to mental health and wellbeing,” he says.

Power says that even with the single fire burning, the odour and its effects are overwhelming.

“You can’t breathe … you get headache … you’re just frustrated and depressed and angry,” he says.

“It consumes your life.”

Community health is something members of the Barro family appear to have an interest in.

Raymond Barro, managing director of the Barro Group, is also a non-executive director of ASX-listed building materials company AdBri, where he sits on its safety, health, environment and sustainability committee. The committee’s objective is: “To assist the board in enabling the group to operate its business safely, ethically, responsibly and sustainably in the communities in which it operates”.

Meanwhile, Rhonda Barro is executive director of Barro Group and a non-executive director of Adbri. She is also a director of the prestigious St Vincent Institute of Medical Research Foundation board, and previously had a long-term involvement with Melbourne-based Italian welfare organisation Co.As.It, whose patron is Victorian Governor Linda Dessau.

Critics say the siblings’ health and welfare stance is in stark contrast to the impact the landfill site is having on the nearby community.

Pham says residents had also asked for help from the Barro Group, but requests to provide air purifiers to affected households had been refused.

“The company has made hundreds of millions of dollars over the last years in other areas of expansion,” says Van T Rudd, who stood for election in St Albans as the Victorian Socialist candidate in 2022. “But still they will not supply air purifiers to the locals.”

A spokesperson for the EPA describes as “astounding” Barro Group’s December admission the last hotspot would take until 2024 to extinguish after previously claiming it was 90 per cent complete. The move came only weeks after the EPA laid criminal charges that, if proven, could attract penalties of up to $360,000 for each director and $1.8 million for the company.

The Barro Group has not disclosed whether and on what basis it intends to defend the charges.

“Compliance has been too slow,” the EPA spokesperson says. “Given this latest information, we have asked for an independent verification of the timelines and we are looking at all legal options available to us.”

A committal mention hearing in relation to the charges has been set for March 31 in the Magistrates’ Court. The Supreme Court is set to hear the Barro Group’s request for a judicial review relating to earlier EPA action on October 3, 2023.

This investigation is by students at the University of Melbourne’s Centre for Advancing Journalism, and co-published by The Age. It is supported by independent media not-for-profit Right Now.