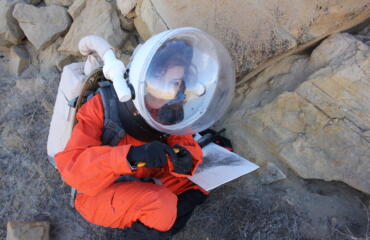

Erica* worked 12 hour days but earned as little as $400 a week. “They made me feel guilty because I have other things to do.” Picture: Silvi Vann-Wall

A young migrant to Australia, Erica* was miles away from her home in Italy when a rare job opportunity materialised. With mounting debts, struggling to improve her English, little bulk in her CV and rising desperation, she took it – but things were not as they seemed.

The job was in direct sales and promised leadership opportunities, visa sponsorship, and a chance to represent some high profile and distinguished Australian charities. These promises masked what turned out to be a miserable reality. Erica’s new job was not what she thought it was. Indeed, it wasn’t really a job. She was being hired under a “sham contractor” arrangement which gave her no rights or entitlements as an employee. By the time she realised the scale of her exploitation, it was too late.

Erica’s typical work day would begin in a Sydney CBD office around 8am, where she was given an iPad and an official-looking lanyard, then assigned a location to travel to and begin her sales work. Sometimes she was told to work on the streets, practicing “charity mugging” – working shopping centres to sign up passers-by to direct debits supporting various charities. Sometimes she would be sent door-to-door in wealthier neighbourhoods. By 8pm she would travel back to the office to report and compare her sales figures with the team, finally leaving around 9pm. She would often be pressured to work on Saturdays too.

She performed all this labour for commission only, earning as little as $400 per week, and was perpetually squeezed to work even more hours.

“They made me feel guilty because I have other things to do,” she said.

Erica’s experience occurred in 2014, but there is evidence that little has changed, with allegations around sham contracting surfacing in the media regularly. The company that hired her was the now-defunct sales firm Genesis Business Partnership. At first glance the company looked impressive, with contractors raising money for a range of respected non-government organisations such as Amnesty International, Bush Heritage, and The Humour Foundation. The company even helped her register for an Australian Business Number, which they insisted was essential for her employment.

Unbeknown to Erica, the company was itself being sub-contracted by the major sales and donor recruitment agency Credico Australia Pty Ltd – a company that’s had numerous allegations of sham contracting raised against it, and was the subject of an action brought against it in the Federal Court by the National Union of Workers.

In 2015, the Genesis team moved from Sydney to Melbourne’s St Kilda Road Towers – which is also the Consumer Affairs-listed headquarters for Credico Australia. Desperate to keep her job, and to gain sponsorship to stay in Australia, Erica followed. She was told by Genesis that accommodation had been arranged for her, but when she arrived, “there wasn’t a bed for me in the hotel room. I slept on an armchair for two weeks”.

Erica said she continued working with Genesis, partly because of the satisfaction gained from helping charities: “For me I was working for that charity, not for Genesis”. But after nine months of erratic schedules and supervisors leaving without warning, she quit and returned to Italy, only returning to Australia in 2017 when she was accepted as a student at the University of Sydney.

The student said she had no idea that the behaviour of Genesis was wrong. The practice of sham contracting – that is, hiring workers as independent contractors instead of employees to avoid minimum wage – is hard to spot if you don’t know the signs. According to the Adero Law and National Union of Workers’ ‘Your Fair Go’ campaign, Credico and similar companies like Appco Group Australia often use outsourced agencies to hire sham contractors in order to avoid paying minimum wage to employees.

Erica said that it was in her nature to stay positive and trust people, so she never suspected anything sinister – and she’s not alone: the ‘Your Fair Go’ campaign has already uncovered hundreds of stories like hers, revealing just how common it is for young workers to have their trust exploited.

Migrants and backpackers represent only a portion of workers who are affected by sham contracting. In 2015, Jessica Guttridge, a young writer from Sydney, said she worked for nothing some days with sales company VMG Global. She took the job out of desperation – “my parents gave me a really hard time when I was neither working or studying”.

Guttridge was recruiting donors for the World Wildlife Foundation (WWF), the National Breast Cancer Foundation, and CanTeen’s regular giving programs.

“I knew it was retail and sales, but I wasn’t too sure what the product was until I came into the interview … I only learnt that it was commission on the day as well.”

She said that as an incentive for recruiting more donors, her managers would entice her with branded socks, liquor and restaurant outings.

The National Breast Cancer Foundation (NBCF) said it hadn’t ever outsourced to VMG Global, but had held a contract with Appco Group Australia, one of the largest donor recruitment agencies in the world, which ended in 2016. When The Citizen contacted Appco to confirm the relationship, a representative said it was also sub-contracting VMG Global for direct sales.

Appco came under fire last year when a $60 million class action was launched against it due to videos emerging of employees being forced to, among other things, simulate sex acts for not meeting sales targets. The class action has also uncovered multiple cases of sham contracting. Despite Appco’s application to have individual cases heard separately, the court ruled last May that the class action would proceed.

“When a donor signs up, the charity pays Appco a fee,” Jessica said, “and then the marketing company and the independent contractor receives a fee … we’d have these papers in the [VMG Global] office that compared how well our teams did with other Appco groups”.

While WWF said it ceased working with VMG Global in 2015, last year CanTeen confirmed it was still raising money via agencies subcontracted to VMG Global, adding in a statement that face to face fundraising was the most effective way of securing ongoing donations. “We conduct comprehensive due diligence to confirm that any agency we work with has practices in place to ensure that fundraisers are paid appropriately and as required by law”.

Emails and calls to VMG Global by The Citizen seeking comment did not receive a response. Genesis Business Partnership was, according to ASIC records, voluntarily deregistered in November 2017.

Despite this, Genesis Business Partnership was still listed as a registered fundraiser for Bush Heritage, Amnesty International, and The Humour Foundation on the Consumer Affairs website last year (the page has since been removed).

Bush Heritage told The Citizen that Genesis had not carried out fundraising for it since 2015. “We perform regular reviews of all the practices of our suppliers and continually carry out due diligence checks on the models of our fundraising agencies,” media representative Nicole Lovelock said. Neither Amnesty or the Humour Foundation responded to inquiries.

“We realise that subcontracting models can provide less protections for workers than directly employing staff,” Lovelock added. Bush Heritage has revised its practices and said it would not be contracting with organisations that use this model in the future.

A spokesman for the ‘Your Fair Go’ campaign said that “practices like those used by Credico are unfortunately widespread in the direct sales industry”. Adero Law partnered with the NUW for their campaign in the hopes it would bring about change for young workers, so that those with less protection like Erica won’t be exploited in future.

Sham contracting practices do nothing to endear potential donors in a climate of increasing suspicion and competition in their sector. In a 2017 report, the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission (ACNC) discovered that public concerns about Australian charities had risen by 42%.

While some charity organisations argue direct sales are an essential part of fundraising in the competitive donor sector, inadequate due diligence checks pose high reputational risks.

ACNC Commissioner Dr Gary Johns said in his 2017 report that positive reception to charities is faltering due to “poor financial controls, inadequate due-diligence, and a failure by charities’ responsible persons to act in the best interests of the charity”. But he also stated that while concerns had increased, it was important to note “that the majority of Australia’s registered charities do the right thing and deliver significant public benefit to our community in a wide range of areas”.

Fair Work Australia, which is currently running a national inquiry into practices in the not-for-profit sector, stated on its website that when respected charities turn to sub-contractors to cut costs, “it’s often employees who pay the price, through underpayment of wages or misclassification as independent contractors, so that the contractor (intermediary company) can offer a lower price”.

With over 54,000 registered charities operating in Australia, it will be a long process to weed out the culprits.

If you believe you have been affected by sham contracting, you can contact the NUW & Adero Law through this website.

*Editor’s note: For reasons of privacy, Erica asked that her full name not be used. Further, the author of this article worked for a brief time with Genesis Business Partnership in 2015.