Eighty years ago, the men of Riverina’s Cummeragunja Reserve became instant heroes by instigating Australia’s first Indigenous mass protest. Today, a descendant says the community’s women also deserve great acclaim.

Tired of the appalling living conditions and the local government’s control of the area, 200 Yorta Yorta people walked off the reserve under the guidance of activists Uncle Jack Patten and Uncle William Cooper.

Yorta Yorta man Shane Charles. He says it was the women who ‘carried’ the community from servitude to the outer world in his grandparents’ time. Photo provided.

At a watershed moment in Australian history, those who left Cummera, as it’s affectionately known, crossed the Murray River into Victoria. While some remained on the reserve to ensure it was not sold off by the government, those who left settled in the floodplain between Mooroopna and Shepparton known as either ‘Daish’s Paddock’ or ‘The Flats’.

Yorta Yorta man Shane Charles says, “It was the first sample of really being free from mission mentality” and would not have been possible without the strength of Yorta Yorta women.

“I guess when you look at Cummeragunja and activists like William Cooper and Doug Nicholls, it was actually the women who were strongest,” Charles says.

“They really held the fort … while the men went off working, they held the family together. That’s why we have so many strong Yorta Yorta women,” he says.

“When you look at the old photos, you’ve got Uncle Doug [Nicholls], Uncle Jack Patten and Uncle William Cooper. But then you look at the women around them… They were there. They ended up leading the charge.”

Born in 1965, Charles grew up on the riverbank and calls both Daish’s Paddock and Cummera home.

“The word Cummeragunja means ‘our home’. I was lucky enough to grow up there. My grandparents grew up there. My father grew up on there. It was a place of safety. It was home,” he says.

Cummeragunja was founded in June 1888 following a successful appeal to the NSW Government for the creation of a new reserve. Residents of the former Maloga Mission had grown dissatisfied with its founder, missionary Daniel Matthews, and his authoritarian and religious approach to leadership.

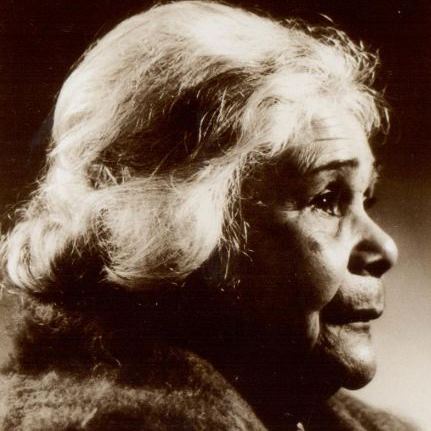

Margaret Lilardia Tucker, better known as Aunty Marge (1904-1996), was one of Australia’s earliest female Aboriginal activists. She grew up on Cummera, the elder sister of Geraldine Briggs. Photo: © State Government of Victoria

The site of the new reserve was chosen in consultation with Indigenous elders.

“The one good thing the Government did was asking the people where they wanted to live,” Charles says.

In the early days, Cummera was a self-sufficient and thriving reserve.

“They had the little dispensary and the nursery. The men were working in the fields.”

Yorta Yorta-led management oversaw successful economic farming enterprises including rice, wheat and wool; with proceeds being directed back into the community.

But this success was short-lived.

The Aboriginal Protection Board and the managers began leasing land to farmers. At one point, 2000 hectares of valuable Murray Pine timber was leased out.

“Eventually the eight to nine thousand acres [3250 to 3650 hectares] got smaller and smaller because the local farmers wanted to take up the land. [They thought] it wasn’t right that Aboriginal people had the land,” Charles says.

In 1915, changes to the Aboriginal Protection Act gave the board greater control of Cummeragunja and its residents. Aboriginal-led management was disbanded with profits from farming now going to the Aboriginal Protection Board, bypassing the residents of Cummeragunja, who were instead paid in rations.

“Every day, it was a dollop of fat or lard – you could smell it from miles away – tea, sugar and flour. And that was it,” Charles says.

Geraldine Briggs (1910-2005) was another Aboriginal rights activist nurtured by Cummera. The younger sister of Margaret Tucker, Geraldine and all her family were involved in the walk-off. Photo: © State Government of Victoria

By the 1930s, Cummera had experienced several deaths due to minimal rations, poor sanitation and cramped living conditions. Diseases such as tuberculosis and whooping cough had become commonplace with life on the reserve.

The arrival of manager Arthur McQuiggan in 1937 made life increasingly hard for the people of Cummera.

“So many managers came through the place and for all sorts of reasons, some were good, some were bad – the last one being McQuiggan. He wasn’t a very nice man … trying to have his way with the young girls and that sort of stuff. He’d send the men off down the back paddock and promise them if they cleared the land it was gonna be theirs. It never was. And all the money that he got was meant to be for our rations … The elders had a meeting and decided this man’s a bad man.”

In an act of defiance, 200 people walked off the station and crossed the state border. Stories of dust flying up as people left were told to Charles’ generation.

“Once we got off Cummera, we were free. It was like the shackles coming off, the ball and chain coming off. Everyone was just so happy. I can’t even fathom [it] when I think about it,” he says.

“All of a sudden, the world opened up … We could determine where we could go and when we wanted to go.”

On the role of women in the walk-off, Charles says, “It was the women who led the charge. They called the meeting.

“It was always said to me by my Dad that the women took the lead. Even though we had Uncle William Cooper who stood up, we had this wave of Aboriginal women come through – your Aunty Marge Tucker and your Aunty Hyllus Maris and Aunty Geraldine Briggs. The women were so strong.”

“Who’s back home looking after the kids? Who’s back home holding the fort? Who’s back home holding the manager off the young girls? The women. It was the women. They held power.

“My dad said to me growing up on Cummera: ‘Afraid of no man son, quite a few women.’

“There weren’t many people who’d take on a strong Aboriginal woman – even still today. So, when I think about that fight, it was shared, and the women carried that community.”

Aunty Marge Tucker, MBE, at the Aborigines Welfare Board in Sydney with a photograph of her birthplace. Photo: Collections of the State Library of New South Wales