Nairi Tchorbadjian won’t tell you she’s Australian. It’s just not that simple.

“I’m an Australian Armenian,” explains the 24-year-old.

“It’s a thing within the community where you identify someone as to where they’re from. My dad is an Ethiopian Armenian and my mum’s side are Lebanese Armenians.”

The Armenian community has had a presence in Australia since the gold rush, but most migrated in the 1960s and 1970s due to civil unrest in Cyprus and the Middle East. Today, there are almost 20,000 Australian residents of Armenian descent. In Victoria, Tchorbadjian is part of a community of 4,500 with Armenian ancestry, of whom only 2,000 speak the language.

“The thing that it comes back to for me is the key turning point in Armenian history, which was the genocide in 1915,” she says.

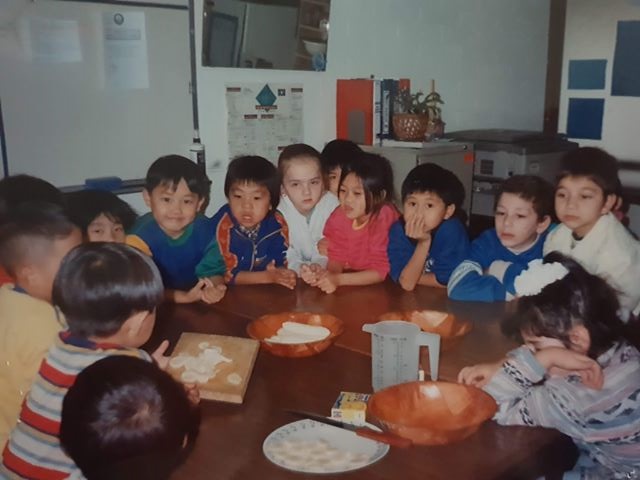

Nairi Tchorbadjian (in white shirt) on her first day of Armenian school, grew up with a strong connection to her multicultural heritage. She continues to embrace these ties today, with a close group of Armenian friends and an Armenian boyfriend.

“The Armenians have fought for their identity for so long, and so in me denying being Armenian I’m thinking, ‘why was there the genocide and why did all those people before me fight and die?’. [It’s why] a lot of song and dance and learning the language is really important.”

Growing up, she was speaking Armenian before she learnt English, traded playdates for weekly lessons on history and culture at Armenian Aginian School, and spent free time playing basketball with the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU). She has an Armenian boyfriend, a close-knit group of Armenian friends and continues to serve the AGBU by sitting on the youth council, Khoomp.

By any standard definition, Tchorbadjian is Australian – born and raised in Melbourne, and while her dad migrated from Ethiopia to escape the revolution, her mum grew up in Sydney. But her nuanced reflections recognise the mosaic embrace of culture increasingly practiced by young first and second generation Australians, a reality captured by the 2017 Multicultural Youth Australia Census.

When questioned on their background, young people of diverse parentage expressed “a rich and detailed picture of hybrid identities and affiliations, not reflected in country of birth or ancestry data”.

Their responses yielded “messy and hybrid” categories of multi-layered, place-based ethnic, religious and cultural attachments.

Members of this generation are no longer bound by simplified notions of “New Australian” identity targeting inclusivity and social cohesion, instead navigating and claiming rich pickings of heritage and upbringing. But for those drawn from minority communities with smaller and more recently arrived populations, finding recognition and identity can be a more burdensome experience.

“It is generally accepted that some of the more settled communities, the larger communities, are more well known and their cultures, traditions and the like are more accepted,” says the chair of the Victorian Multicultural Commission, Vivienne Nguyen. “It’s a factor of time, a factor of size and a factor of their ability to advocate.”

Meanwhile minorities large and small continue to encounter social attitudes that remain stubbornly resistant to embracing diversity. A 2018 survey commissioned by SBS, one of the largest conducted on racism and prejudice in Australia, indicated that almost 49 per cent of respondents wanted minority groups to behave more like mainstream Australians. Some 41 per cent believed the country was weakened by people from different ethnicities sticking to their old ways.

Diversity and discrimination are cited in the top three concerns of multicultural young people, with over half of the respondents in the MY Australia Census experiencing unfair treatment in the single year leading into the study, and Nguyen believes members of smaller minorities face the worst of it.

Providing programs and policies to help newer arrivals and smaller communities find their way can only go so far in overcoming these obstacles, she argues. What’s required is a shift in the social mindset, a recognition that embracing multiculturalism and Australian values are not mutually exclusive concepts.

“Freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, of the press, of religion, respect – it doesn’t matter where you came from originally, when you are here in this country, you embrace those values,” says Nguyen.

Pushing the boundaries of cultural understanding beyond the larger, familiar cultural groups is pivotal to achieving that shift, she says – a sentiment echoed by Tchorbadjian.

“Being Armenian is such a minority, people just aren’t educated as much about it. It’s not like being Greek and Italian, where people already know about the country and the culture,” she says.

“I guess if I were to have grown up in say, Lebanon or LA, where there is a bigger Armenian community, possibly my connection could have been different because of the frequency of events and how often I’m around [other Armenian] people,” Tchorbadjian says.

“Sometimes I wish I didn’t have to always explain, but I’m still proud because I might find someone that will actually ask me about [being Armenian].”

Zara Akpinar’s connection to her culture grew stronger when she travelled to her father’s hometown of Kayseri, Turkey in 2013. (Image: Supplied)

Culturally speaking, the journey of Hobart student Zara Akpinar, 21, who grew up with little connection to her Kurdish heritage, could not be more removed from Tchorbadjian’s story. And yet as young women, they find themselves in a similar place, claiming their histories.

“I wasn’t really raised in a Kurdish culture,” says Akpinar. “My mum’s Australian and we mainly grew up around her side of the family because there’s not a big Kurdish community here. The only exposure I got to my culture was my dad, and he didn’t really teach me that much.

“I think when you come from a minority group, especially one that’s been oppressed, there’s probably a lot of trauma associated with teaching your kids about it,” she says.

“So possibly that’s why I didn’t really get that influenced by [being Kurdish].”

Akpinar continues to visibly practice her Kurdish culture each year in celebration of Newroz, Kurdish New Year. Image: Supplied

Kurdistan was divided at the end of World War 1 among regions in Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria, where the culture faced suppression. Many members of the community migrated to Australia in the 1960s, with refugees escaping the Iran-Iraq War and Gulf War arriving some decades later. They now form one of the smallest minorities in Australia.

According to the 2016 census, just over 10,500 people have Kurdish ancestry and around 6,000 actively speak the language. And with most of the diaspora split between Melbourne and Sydney, the presence of the culture in Tasmania is microscopic. One source estimates just 37 Kurdish people live in the state.

Research by the Australian Research Alliance for Children & Youth has long recognised the significance of culture in the development of the identity and self-esteem of young people – and having an accessible community strongly influences this outcome.

Without the visibility of the Kurdish community around her, Akpinar took her evolving interest in her heritage to the internet and began regularly visiting her extended family in Melbourne to celebrate cultural festivities including Newroz, Kurdish New Year. But the lack of mainstream awareness and understanding of her minority culture meant sacrifices were made in the formulation of her identity.

“I think being mixed you feel like you’re not enough for either side. I just feel like I don’t fit in, not completely,” continues Akpinar. “Especially because I don’t speak the language, even though I understand a lot of it, I can’t really communicate. There’s not a lot of resources, not compared to the mainstream languages that a lot of people can learn.”

“It is quite different being a minority, especially ones that don’t have a country or that not many people have heard of,” says Akpinar.

“It can be quite difficult to have to explain who you are all the time.”

She’s nonetheless found her way to an embrace of her Australian and Kurdish identities, one which has enabled an activist interest in her ancestry to blossom.

“I feel proud to live in Australia, especially all the opportunities it gives me,” she says. “I have freedom of speech. I can actually speak about Kurdish rights and issues that are happening, unlike a lot of Kurdish people around the world that can’t speak up because they’ll be imprisoned or discriminated against.

“So yes, I feel proud to be Australian, but I’m also proud to be Kurdish as well.”

Jason Lee (red and blue jumper) migrated from Thailand when he was two-years-old, and has been forced to balance his traditional Hmong heritage with a modern Australian culture ever since. Image: Supplied.

For others like Jason Lee, a 32-year-old project manager living in Melbourne’s north and a first generation migrant, it’s been a tougher battle to publicly share and claim his cultural story.

Lee belongs to one of Australia’s newest minorities, the Hmong community. While Hmong people descend from nations across Asia including Vietnam, Thailand, Myanmar and southern China, the Australian diaspora is largely comprised of Laos refugees, who migrated to flee persecution from the communist revolution in the mid-1970s. Today, the tiny minority sits at around 2,000, with the vast majority settling in Queensland.

When Lee migrated from Thailand with his family 30 years ago, nothing was more important for his Laos-born parents than keeping connected to their traditional culture.

“I had a very strong Hmong childhood growing up,” says Lee. “Coming into such a good country, [my parents] tried to focus on and pushed me to study and keep the culture. They taught me the wedding and funeral processes, all the cultural stuff that is required in life.”

“But it was quite difficult because my parents had that traditional background and so it was very hard for them to adapt to modern society.”

Lee explains that Hmong people are largely guided by customary beliefs that value respecting and honouring the family unit. He also practices traditional Hmong spirituality, which involves a shaman performing various ritualistic, healing and communication roles. Lee’s father sits high up in the Melbourne Hmong community and his brother is undertaking study to eventually be considered for the same position.

As a teenager growing up in suburban Melbourne, Lee’s strong ties to his Hmong culture were sorely tested – a painful passage familiar to most first and second generation migrants.

“My parents are not very modernised and they have very little English. It was a bit of a battle [growing up] because we were first generation,” explains Lee.

“When I was 15, I had blonde hair and to them, I became a bad person. You either dyed it back to black or you were disowned. With Hmong people, it’s a lot about respect and saving your face as a family,” Lee continues. “It’s just things they have never experienced and haven’t gone through so they can’t accept that it’s normal.”

Despite clashing value systems proving difficult to balance, as he has matured Lee has embraced his Hmong roots. He serves as vice president of the Victorian branch of not-for-profit Hmong Australia Society Inc, which aims to celebrate and unite the community and ensure young members are guided to proudly involve themselves in their culture.

“I do try and maintain the culture very strongly,” says Lee. “But there are activities that I’ll do outside of the Hmong culture as well. I like the footy, I like travelling, I’m into my soccer.”

Every time he ventures into the mainstream, he recognises risk, but resolves to chip away at it by making the effort, sharing his cultural story when he can.

“I think you have to accept that once you walk outside, there are people that are going to look and discriminate against you because you’re Asian. It’s normal,” he says.

“I’ve always had that mindset [to] just want to make it better.”

Research for this story was supported by a fellowship from the May and Romeo Schiavon Journalism Fund.