In the darkness, when most of us have already sunk into the depths of the night, some are just starting their day.

At 11 o’clock every night, Chengbei Wet Market, the largest vegetable market in Rugao, Jiangsu Province, is at its busiest. The exchange of bargains, the beeping of mobile phone receipts, the roar of tricycle movements, and many other noises merge; breaking the silence of the night. At the market’s entrance, a long queue of trucks wait to unload cabbages, tomatoes, potatoes, onions, and other vegetables, as workers unload the produce.

In this market, there is a group of workers who work from midnight until dawn and only sleep four or five hours a day. This is their life. Some are wholesalers, busy sorting vegetables, counting and selling; some are truck drivers who drive from all over China to bring tons of vegetables to the market; some are workers who unload and carry vegetables, constantly carrying baskets of vegetables to the warehouses; and some are vendors from other markets, buying vegetables, bargaining and transferring them from Chengbei to other markets and eventually delivering them to the tables of millions of people. They work all year round, except for New Year’s Eve. Even in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic, they work tirelessly every day to ensure that every family has access to fresh food and vegetables.

“The market has become my second home,” said WuJiu Zhu, a 53-year-old truck driver who has worked at this wet market for 30 years.

“Every day, I drive to other parts of the country to buy food, and then I sell it at the market in the evening.”

He has just finished a 19-hour drive from Inner Mongolia, the northernmost part of China, to Jiangsu province, in southern China. He and his coworkers brought 15 tonnes of garlic leaves, potatoes, and tomatoes to the market. They will leave again for Shandong the next day.

“Every day we sleep in the truck, not at home, for only five hours a day,” Zhu said.

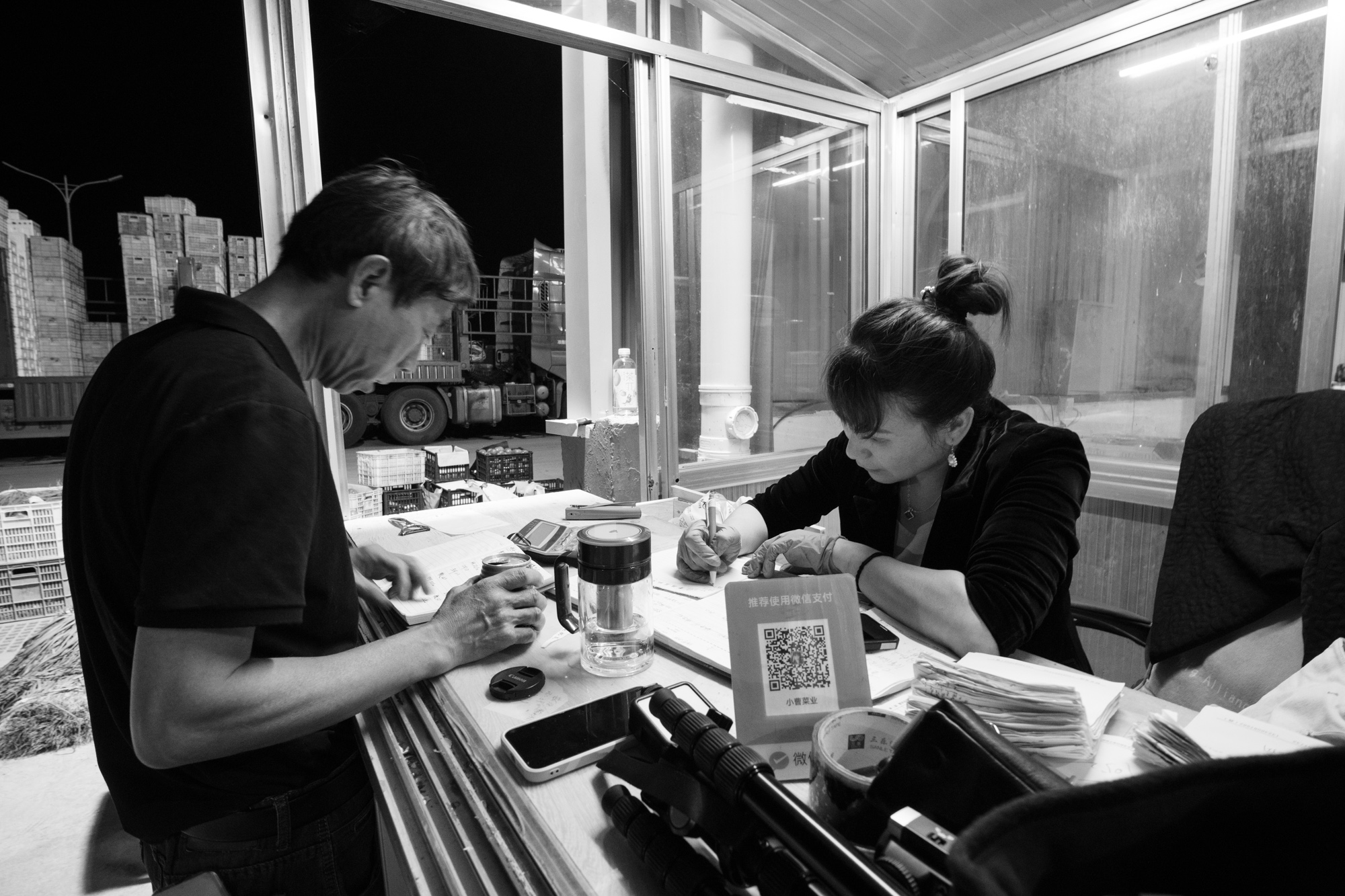

Wenxuan Wang, WuJiu Zhu’s wife, runs a wholesale vegetable business with her husband. Wang is busy counting, sorting, and haggling with the vendors when new vegetable deliveries arrive at the market

“We have no choice but to rely on this market to feed our families. From July to October, the peak season, we can sell 100,000 pounds of potatoes and tomatoes a night, so it’s better to work hard than not make any money,” Wang said.

Over the past few years, recurring outbreaks of the Covid-19 pandemic have made it harder for vegetable suppliers like Wang to do business. Due to travel restrictions imposed by the government, they are often unable to travel out of the province to buy vegetables and customers are unable to come to the market.

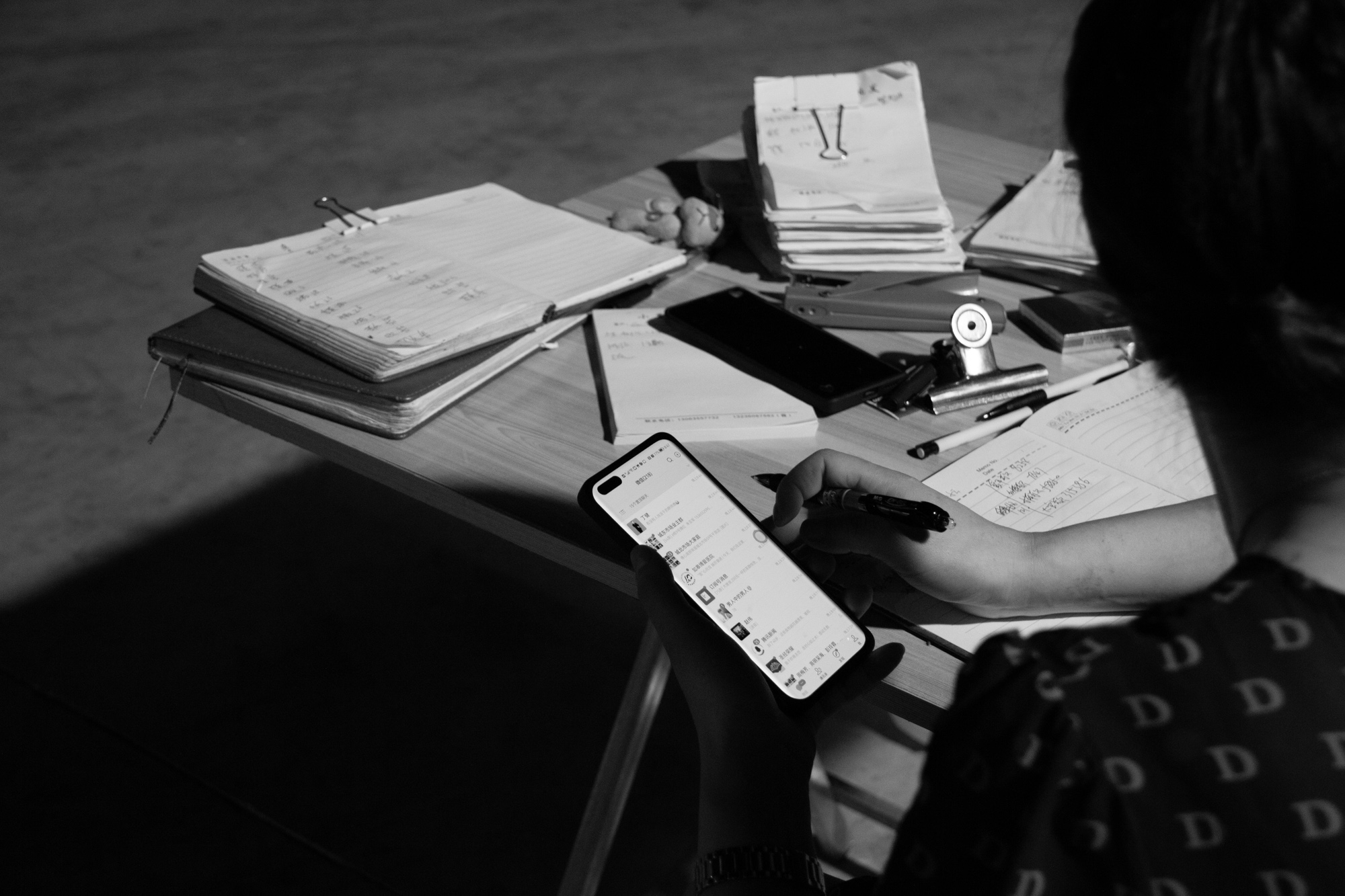

“There’s nothing we can do but follow the government’s policy,” she said, as she tapped her calculator quickly and wrote down a dense string of numbers in her ledger.

The market has brought lots of job opportunities to this ageing city, despite the number of people employed in Rugao dropping sharply from 2016 to 2021. The people who work here, most of whom have not received a high level of education, include couples who dropped out of high school, retired military personnel and migrant workers who have never received an education.

“Who doesn’t dream of bright lights and big cities?” said Yiqi Jia, one of the youngest workers at this market, as he lugged around a load of veggies.

“But people won’t hire us without degrees. The night shifts may be tough, but at least we’re able to pay our bills.”

However, the chronic lack of sleep has also caused many people to suffer from various degrees of “occupational diseases”: serious dark circles under the eyes, hair loss, neurasthenia, and more. For the night workers, living in the market is not just about the brightness of vegetables and the security of an income, but also the bitter cold of winter, the mosquitoes and sweltering heat of summer, and the constant worries about vegetable prices, storage problems, logistics and transport.

As the lights in the market dimmed with the dawn, the city began to wake up and the big trucks left the market one by one. The crowds dispersed and the only signs of what had happened were a few vegetable leaves on the ground.

In this portfolio, I concentrated on a group of night-time wet market workers who, for the most part, represent China’s lowest level of labourers. I believe that every worker in the wet market deserves respect and attention and that without their tireless labour day and night, the population would not be able to enjoy such delectable meals every day.

My main goal is to bring attention to the real lives and human rights of the workers by telling their stories. The seemingly dirty and messy Chengbei Wet Market has become the economic lifeblood of the town and an indispensable part of the old city of Rugao. As China continues to deepen its economic reforms and urbanisation, this historic market has survived and become a place for the city’s residents to rely on. It has saved the city’s economy by creating jobs for its people.

I chose to take black and white photos for this project to better represent the theme of ‘working in the dark’ and to focus on a variety of market workers.

I was inspired by the photographer Elliott Erwitt and his black and white candid photos of ironic and absurd situations in everyday settings, particularly his ‘Dogs’ and ‘Public Figure’ topics. The perspective of some of my portraits tried to mimic the angles he used when he took ‘Public Figures’. For example, for the portrait of Yiqi Jia, the young porter, I studied Elliott’s 1959 photo of Buckminister Fuller, and for the perspective of the truck driver, I imitated Elliott’s 1953 photo of Jack Kerouac. I also tried to include a dog photo in my portfolio.

I like the composition of the photographs of Robert Frank and David Burnett. I like the way they split the images and the composition they use when taking portraits. In capturing and photographing the facial expressions of people, I was inspired by Pedro Luis Raota’s “Faces of Life” portfolio. His photographs are so vivid and artistic, and I love the way he blurs the background to highlight the people, which made the photos look like sketches.