‘Paul’ is a bit hazy about precise dates but he remembers the day in September last year only too well. His wife was hanging out the washing and he was inside reading to one of his four children when he blacked out. Three days and three more seizures later, he found himself entering a whirlwind of doctors’ appointments and treatments for aggressive brain cancer.

Paul says he pretty much walked away from the first operation but the side effects of the second shocked him. Standard chemotherapy and six weeks of radiation didn’t appear to help and so in May this year, Paul chose to enter a clinical trial for a new experimental therapy.

Once a week, for six weeks, he got out of bed at 6am so his wife or a friend could drive him the four hours from western Victoria to Melbourne. Even though it was a long trip and made for a long day, and the traffic drove him mad, Paul was pleased to get to the Royal Melbourne Hospital where a dedicated team was ready to take care of him.

Within an hour of arriving he would be in his chair and hooked up to the experimental treatment that aims to target and kill his cancer, Glioblastoma Multiforme, a disease of many names and one deceptively innocent abbreviation, GBM.

Although GBM is a relatively rare form of cancer, it is the most common and most aggressive of brain cancers. The targeted therapy that flowed into Paul’s veins was the result of decades of medical research and painstaking development.

Paul, who worked in mining and is in his 40s, is a practical guy with a practical credo: you do whatever you can to keep living and you stay positive. He says he doesn’t know if the treatment will work but he feels it represents something new, something that hasn’t been tried before, and is the right option for him.

Across all cancer, decades of work have given Australians with the disease a 66 per cent chance of surviving for five years, compared with just a 47 per cent chance in 1982.

Access to options for people with cancer, including trials of this nature, is also a key for Paul’s doctors and nurses, a point stressed repeatedly by Professor Mark Rosenthal, director of medical oncology at Melbourne Health.

“It doesn’t matter where they come from, from western Victoria or Flemington,” he says in a no-nonsense interview squeezed into his packed schedule. “Doesn’t matter,” he repeats. “Everybody deserves the right to be offered a clinical trial.”

Rosenthal speaks quickly, every sentence precise, to the point. It is clearly a matter of pride to him that he can offer many of his patients the newest experimental drug because of the global reputation of the Brain Cancer Group at Royal Melbourne.

“What I like about having a trial portfolio at Royal Melbourne… [is that] patients don’t feel they need to have won TattsLotto to fly to New York to go on some fancy trial. They can get it at Royal Melbourne,” he says.

“We can say for a number of our studies we’ve had the first person in the world ever to get a particular drug. I think what it does is offer the opportunity for a patient to be that person.”

It is a reality Paul embraces. He says he’s “a great believer in using the experts” and feels confident he is getting the best possible attention. “When I first spoke to Mark he gave me a big printout and he said ‘This is what will happen. If this doesn’t work, we’ll keep moving on.’ So you appreciate the plan.”

Some cancers, such as Paul’s, are not common but having cancer of some kind is something one in two Australians now experience at some stage in their lives. Increasingly, though, these people and their families are helped by discoveries from research and clinical trials that offer new approaches to preventing, detecting and treating cancer.

TREATING CANCER: Clinical trials in Victoria *

26 hospitals run trials

2279 new people entered a trial in 2012

6–7% of people with cancer have been recruited into trials in Victoria over the past 25 years

Six-out-of-10 trials were sponsored by industry in 2012

Across all cancer, decades of work have given Australians with the disease a 66 per cent chance of surviving for five years, compared with just a 47 per cent chance in 1982.

This continuing search for new and better treatments is clearly a global effort but the part played by Australian researchers and clinicians in this field, as well as more broadly in medical research, shouldn’t go understated. Decades of work here, particularly in Melbourne, has made substantial inroads into treatments for cancer and other diseases and conditions.

Ironically, these gains are not widely appreciated in the community, in part because their promotion, particularly through media reports of “breakthroughs” and “cures”, carries with it the risks of unrealistically raising expectations.

The struggle to balance optimism and expectation was highlighted recently in the Federal Budget with the plan to use most of a proposed $7 patient co-payment on bulk-billed visits to the doctor for a $20 billion “Medical Research Future Fund”. In his Budget speech to Parliament, Treasurer Joe Hockey raised the possibility that because of the fund “…it may be an Australian who discovers better treatments and even cures for dementia, Alzheimer’s, heart disease or cancer.”

A fractious Senate will decide the fate of the measure but at the very least it has focused public attention on a substantial issue. Whatever the outcome of the Senate vote – and the proposed research bank – researchers are in no doubt that continued funding is essential to maintain Melbourne’s research and clinical trial momentum.

In 2011, concern that funding cuts would threaten medical research – and by inference the health of Australians for decades – prompted the launch of the “Discoveries Need Dollars” campaign and “Rally for Research”. Dr Krystal Evans, of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, led the Melbourne rally. She says that continued research funding is needed to address Australia’s future big health issues. “Research can’t be turned on and off like a tap,” she warns.

Well-funded medical research has a more immediate value than the dream of a cure sometime in the future. Victorians are already reaping the advantages of living near one of the world’s premiere sites for early clinical trials. Right now, people with cancer gain access to experimental drugs and treatment options at major sites in Melbourne and other smaller sites around the state.

Royal Melbourne Hospital (RMH) is one of Australia’s major cancer trial centres. Sit in the waiting room of the RMH oncology day centre and you will find a place of calm, with people reading magazines, chatting and smiling. It’s likely the only clue that the people waiting here are living with cancer is the presence of an occasional bandanna-wrapped head. The day centre is in an ageing section of the hospital and its days are numbered, with its future shape lying somewhere in the massive construction site for the Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre (VCCC) on the other side of Grattan Street in Parkville.

A hospital’s size is usually measured in beds, but the size of the oncology day centre is measured in chairs, 16 in all, of which only three are dedicated to the clinical trial group. It is in these three chairs that people in one of Royal Melbourne’s 70-odd cancer trials sit while receiving their treatment. Professor Rosenthal says this number of trials represents a large portfolio.

“The advantage is that we’ve got a large clinical trial portfolio across many of the cancer types. In brain cancer in particular, we’ve got a very strong portfolio of trials at Royal Melbourne and a good network within Melbourne, so the patients are referred backwards and forwards between centres,” he says.

“We’ve got maybe half a dozen brain cancer specialists in Melbourne, like myself. But we know who’s doing which trials and if a trial is applicable at Monash, I’ll send a patient to Monash. If there’s a patient at Monash, they’ll send them to me.”

► Glioblastoma multiforme or GBM

• About 1% of all cancers

• A glioma or glial cell cancer

• The most common of malignant gliomas (60-70%) and most aggressive

• About 1-in-3 GBM tumours has genetic changes for epidermal growth factor receptor VIII (EGFR-VIII)

► Symptoms may include

• Headaches

• Nausea and vomiting

• Seizures

• Stroke-like symptoms such as weakness and blindness

• Problems with thinking, memory and reasoning

► Living with GBM

• Ave survival is 1-to-2 years with best standard care

• About 1-in-4 (27%) of people survive beyond 2 years from diagnosis when treated with radiotherapy and chemotherapy

• Age, location and type of tumour, and general health all impact survival

Source: Cancer Council Australia

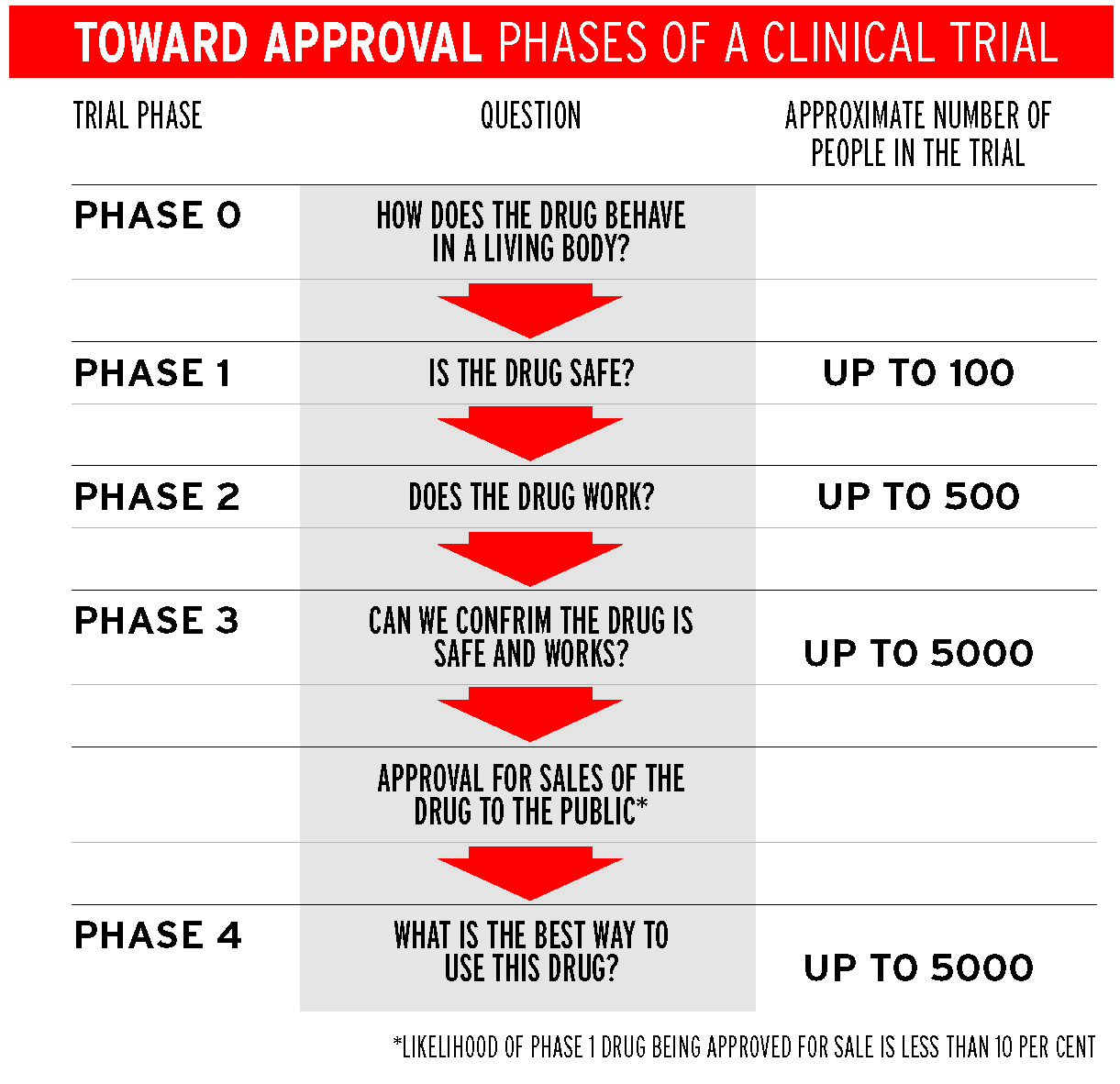

Rosenthal says that about one-third of the trials at Royal Melbourne are for experimental drugs or new therapies that are tested in Phase 1 trials, the first in the hierarchy of medical trials in which people receive the treatment. These trials tend to be run at big hospitals such as Royal Melbourne, Peter MacCallum and Austin Health.

Melbourne’s largest cancer services have had a welcome injection of infrastructure thanks to the fact that governments tend to construct buildings to encourage growth. The Olivia Newton-John Cancer and Wellness Centre at Austin Health was completed in 2013 and from 2016, the VCCC in Parkville will house the merged cancer services of the Peter Mac, Melbourne Health and the Women’s Hospital.

Rosenthal is looking forward to the new Parkville facility. “When we come together in a year and a half, hopefully it’s bigger and better and we’ll be comparable to any major Phase 1 early phase trial group in the world. And that’s opportunity for our patients.”

Melbourne’s research and clinical trial scene is not just about gleaming new buildings. It is the calibre of Melbourne’s researchers and clinicians combined with best-available equipment and techniques that create the research momentum that delivers benefits for people living with cancer. The roots of this momentum run deep. Decades of work have built the networks of medical researchers and clinicians with the knowledge and reputation to attract the biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies so important to commercialising medical research and running early stage trials.

One of the pioneers of medical research in Melbourne is Professor Donald Metcalf. Recruited from Sydney by Walter and Eliza Hall Institute 60 years ago, Metcalf is now 86 but still at work, his focus undiminished. “Melbourne is one of the big cities in terms of medical research, a bit like Boston, a bit like Stanford, California,” he says. “There are great numbers of people and goodness knows how many institutes.

“For some reason, which none of us can understand, Sydney has not developed the same outstanding institutes that Melbourne has had for 50 years. I think these things have a snowball effect. Once you’ve got several [institutes], you’re more likely to get more and more of them.”

Metcalf’s research is widely regarded as the biggest cancer treatment success story to come out of Melbourne, success that he attributes to his stubborn nature. His work on molecules in the blood, called colony stimulating factors (CSFs), that activate the immune system has helped more than 20 million people with cancer around the world.

Metcalf discovered four CSFs. One of these stimulates white blood cells called granulocytes and is known as G-CSF. This molecule helps people survive the harsh chemotherapy that is more likely to kill their cancer cells, and SO can extend their lives. “It’s very difficult to say how many people are alive today because of [CSFs] but what they were finding was that most people couldn’t stand the chemotherapy, the sequential chemotherapy, because they didn’t have any white cells. And so the use of CSFs has allowed people to complete their treatment.”

Few researchers are able to say they have helped millions of people but Metcalf and his colleagues are among them. You have to lean forward to hear Metcalf most of the time, and when asked what it’s like to help so many people, his voice lowers. “It’s a bit embarrassing. Wouldn’t you feel embarrassed if someone in the audience put their hand up to say ‘You’ve saved my life’?”

Metcalf’s work is still adding to the momentum of the snowball he cites.

Professor Donald Metcalf

PIC: The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research

Amgen Australia was the biotechnology company that helped develop G-CSF from discovery to treatment. Dr Anthony Treacy, the Clinical Operations Manager at Amgen Australia, says the company began its collaboration with Metcalf and Royal Melbourne 20 to 25 years ago when it was first set up in Australia. Parent company Amgen Inc is now the world’s largest biotechnology company. Treacy says G-CSF is used in treatments for many different types of cancers and without the G-CSF treatment, people would tend to become weak or catch infections and sometimes die.

Treacy says that as a result of the work at Royal Melbourne the hospital is recognised by Amgen Inc as one of the four or five sites across the world where the company chooses to run early phase clinical trials. “My bosses, bosses [in California], are aware of the good work that goes on at Royal Melbourne,” he says.

The success of CSFs has had other flow-on effects in Melbourne and Australia. Marcus Clark, the chief executive of Cancer Trials Australia (CTA), says clinicians who were key players in creating CTA coordinated the trials of the G-CSF in the 1980s with CTA growing off the back of those trials.

“We’ve done exit interviews of patients when they’ve come off trials and I don’t think anyone has ever said ‘I wish I hadn’t been on a trial’.” — Mark Rosenthal

CTA now co-ordinates multi-site cancer trials and provides networks for researchers and clinicians. He says the trend is for the global pharma and biotech industry to only award early phase trials to “centres of excellence” and Australia has positioned itself to attract that rating.

“By being centres of excellence patients get access to products, albeit in clinical trials, that they wouldn’t otherwise get,” he says. “Some of these new molecules that are interfering with cell targets or cell pathways have proved highly successful and patients will continue to get access to this if Australia is seen to be the place to go, to be part of the early phase clinical trial.”

Even though Australia’s high dollar and low population mean it is less competitive for Phase 2 and 3 trials, Australian governments can see the immediate advantages of Phase 1 trials and have worked to streamline processes to approve such trials.

Mark Rosenthal says the Government wants to increase the numbers in clinical trials to 15 per cent of all cancer patients. At the moment, 11 per cent of Rosenthal’s patients go onto clinical trials, which is nearly double the Victorian average. Unfortunately, there is unlikely to be a suitable trial for every patient.

“We don’t just take [a trial] off the [laboratory] bench and flick it their way. It’s got to be the right trial for the right patient and the right patient for the right trial.”

Early phase clinical trials are about more than just access to experimental drugs. Rosenthal (pictured right) says a huge amount of data suggests that being in a clinical trial has significant health benefits for patients, although improved survival is difficult to show and has not been proven definitively.

Another benefit is the simple fact that patients like being on trials. “They like the attention to details, they like the extra care that they get. In an ironic way they get tested more frequently so they are assured of where things are going. They’re trying something a bit more experimental,” Rosenthal says.

Megan Smith, the Oncology Research Nurse running Paul’s clinical trial, says people in cancer trials are assigned a dedicated team, including their own nurse and doctor. While patients like receiving this individualised care, Smith also likes giving it. “I love the job, I love it,” she sings. “I used to be in mainstream day care before I came here. I loved it there but I really love the specialised care that we give and we get to know the patients. It’s rewarding. It’s quite special.

“We’re not just there putting up the drug and checking their blood. We’re solely looking after all aspects of their care. If they need social work, if they need physio, if they need palliative care, if they need admission for anything, then we can organise that.”

Smith adds: “We’re assigned to them, we’re chasing everything up, we’re ringing them to make sure they’re okay and patients love that, I think.”

Rosenthal makes the same point. “We’ve done exit interviews of patients when they’ve come off trials and I don’t think anyone has ever said ‘I wish I hadn’t been on a trial’.”

He is determined to live up to his commitment that every patient in Victoria who qualifies gets equal access to his trials and has done a follow-up review of the trials to make sure that it is the case. “There’s no difference between non-English-speaking or English-speaking [people], whether they get onto a trial. No difference between public and private as to whether they get onto a trial. No difference in terms of … social placement, top to bottom, Toorak to Hoppers Crossing. It doesn’t matter where you come from, you have an equal chance of going on a clinical trial at Royal Melbourne. I think that’s incredibly important.”

People like Paul who need to travel from regional Victoria are given even more support so they won’t miss out on the opportunity. “I’ve got to come down here for blood tests and ECGs in two weeks,” says Paul, on a recent visit to Melbourne. “But they will put me up in accommodation for three days when I’m here, so that’s fine. And the wife comes, so yeah, I miss my kids but you know, I keep punching.”

Fine-tuning of awareness campaigns, detection and treatments [for breast cancer] have improved the 10-year survival rate from 64 per cent to 83 per cent over the last 20 years . . . [T]he five-year survival rate for bowel cancer improved from 48 per cent to 66 per cent, while kidney cancer survival rates rose from 47 per cent to 72 per cent over the same time frame.

Reflecting further, he adds: “Everyone here’s been fantastic. They explain things to you well and I’m very happy to be on [the trial].”

Paul’s cancer, GBM, is the most common of the cancers in glial cells, which are the cells that protect and support the rest of the nervous system. The survival rate for the general population averages around seven months, although this can vary, with some patients surviving for longer than expected. Rosenthal (pictured right) says with the best possible standard of treatment, survival is now around 12 to 14 months although there have not been any dramatic improvements in survival for people with GBM.

“There have been incremental improvements. Probably for the younger, fitter patients, survival definitely improved but for the older patients probably not,” he says.

Incremental improvements should not be undervalued. Many people with cancer live longer today than they would have even 20 years ago. This extension of life is not because of the flashy “breakthroughs” often touted in the media, but because of decades of research baby steps that explored ways to prevent, detect and treat cancer.

Breast cancer is a typical and well-publicised example. Fine-tuning of awareness campaigns, detection and treatments have improved the 10-year survival rate from 64 per cent to 83 per cent over the last 20 years. Some cancers such as pancreatic and mesothelioma have very low survival rates, but the five-year survival rate for bowel cancer improved from 48 per cent to 66 per cent over 20 years, while kidney cancer survival rates rose from 47 per cent to 72 per cent over the same time frame.

The traditional approach to cancer treatment relies on chemotherapy and radiation therapy but these kill many types of cells in the body and cause many of the unwanted side effects. The idea behind the newer experimental cancer treatments is to target the specific pathways within tumour cells using molecular therapies, often made of protein using biotechnology techniques. Rather than killing any cell in its path, ideally these therapies will leave healthy cells and tissues undamaged.

Dr Lawrence Cher, an oncologist at Austin Health, says survival had improved for people with GBM about nine years ago when doctors tweaked traditional treatments and added chemotherapy combined with the standard radiation therapy. “What they were able to show is that there was an improvement of two-year survival from about 10 per cent to 25 per cent, which is quite significant.

“Since then, people have been looking at a whole lot of other types of treatments, . . . trying to target specific molecular pathways within tumours. To date, that has not come up with the perfect answer.”

Austin Health is also running clinical trials for targeted therapies for GBM. One trial is an early Phase 1 trial of a targeted therapy based on original research from Austin Health. Cher is also part of a Phase 3 trial that is trying to boost the immune system using a vaccine to attack and kill GBM cells in a specific group of tumours with a unique mutation targeted.

“It’s a way of looking at treating these sorts of tumours in a very different way than we’ve done in the past with radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Obviously the patients are getting both radiotherapy and chemotherapy but we’re just adding this in to try and improve the treatment,” Cher says.

The Austin trial is also combining the targeted therapy with another of Donald Metcalf’s CSFs that stimulates both granulocytes and macrophages (another type of immune cell), called GM-CSF. Rather than helping patients to survive harsh chemotherapy in the way G-CSF does, the purpose of the GM-CSF is to promote killing of the brain cancer cells by stimulating the immune response to the vaccine.

Paul’s tumour contains a genetic change for a molecule called Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor VIII (EGFR-VIII), which is present in 30 per cent of GBM tumours. The approach used for Paul’s treatment began with researchers looking for the genetic changes in EGFR-VIII in his tumour cells. Once those changes were found, Paul could be given the specific targeted treatment to try to kill those cells. These targeted treatment approaches are what have become known as “personalised medicine”.

“I’m happy to be on the trial because you don’t know where it’s going to lead you. Could be bad, could be the best, but I’m still here, so I’m happy. And I reckon you’ve got to be positive otherwise it’s a waste of time. So I’m positive and that’s it.” — brain cancer sufferer ‘Paul’

Even though the full benefits of personalised medicine are still some way off, Paul and many of the people on clinical trials are also keen to contribute to the long-term aim of finding treatments that will help people to live longer after a cancer diagnosis. “I’m happy to help someone else along the way,” says Paul. “Good luck to them.”

Paul knows the GBM trial he is on might not be the answer to his health problem but he is confident his doctors are doing their best and are keeping him informed.

“I like [my doctors] because they don’t give me bullshit. Both of them, Professor Day and Mark [Rosenthal] are pretty straight down the line and I appreciate that because I don’t want to, you know, be given false hope.

“I’m happy to be on the trial because you don’t know where it’s going to lead you. Could be bad, could be the best, but I’m still here, so I’m happy. And I reckon you’ve got to be positive otherwise it’s a waste of time. So I’m positive and that’s it.”

* Paul’s real name has been withheld.

FURTHER INFORMATION

The Victorian Cancer Trials Linkwebsite provides:

• Fact sheets

• Searchable database of clinical trials for cancer

• Searches can be narrowed to help match people with relevant trials

• Printable trial information to discuss with doctors

ALSO

Cancer Council Victoria Helpline (ph: 13 11 20) has an experienced cancer nurse who can explain clinical trials. Advice is also available with the help of an interpreter.

► An edited version of this story was also published in The Age.