The internet democratised news media to such a degree that it became common for readers to expect interaction and debate with journalists and other readers in a way they never expected to before — almost instantly through online comments.

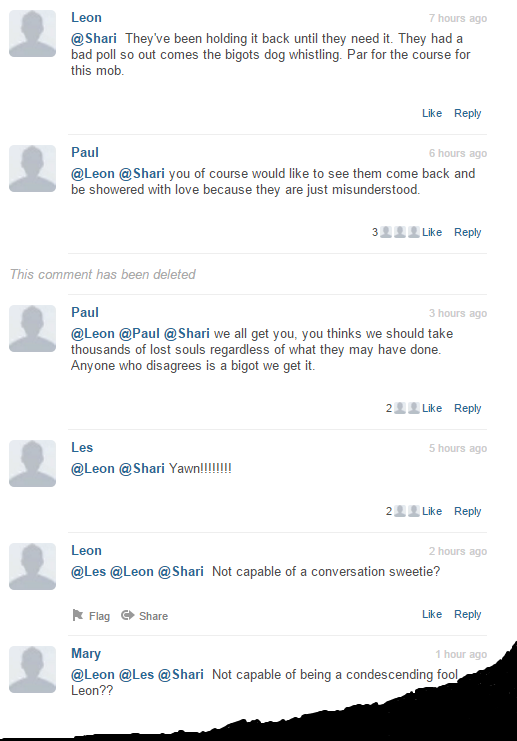

Comments sections morphed from a kind of digital-age Letters to the Editor space into something that was much harder to filter and control.

They developed a bad rap, especially among writers. “Don’t read the comments” is now a catchphrase, a cynical warning to journalists venturing below the line to expect ignorance, anger and abuse. They are “where all the world’s unhappiness dwells,” as British journalist Caitlin Moran has put it.

Faced with an an ever-increasing volume of comments and lack of resources to moderate them, some sites, including CNN, Reuters and The Daily Beast, have decided to throw in the towel, ditching their comments sections and pushing public debate onto social media.

This retreat prompted some to suggest that the notion of free and open comments has passed its use-by date.

“A lot of news organisations are turning off their comments, which isn’t something we’re doing . . . We want to see them become a genuinely useful insightful space to complement the journalism, rather than just having them disappear.” — Mary Hamilton, the Guardian’s executive audience editor

But many news publishers still want the positive and constructive engagement they get from the best commenters — and the potential advertising dollars that come from having a bank of loyal readers. They just need new ways to clamp down on vitriol without stifling debate.

Jennifer Beckett, a former comments moderator at the ABC and now university lecturer, saw first-hand how poisonous reader interaction could be.

“There were some days when I would come home and need a scalding hot shower,” she says. “You’re soaking in some pretty heavy stuff.”

Now, a number of researchers, journalists and digital agencies are looking at new ways to push comments into a more positive future, in what could mark a turning point for audience engagement.

The New York Times, Washington Post and software developer Mozilla are working on The Coral Project, a collection of open-source apps designed to help publishers manage their communities, while the Engaging News Project at the University of Texas is researching techniques to help news media better connect with readers.

The Coral Project unveiled its first app, Trust, last month at the South by South-West (SxSW) festival in Austin, Texas.

Trust, which will be tested first by the Times and the Post, helps news outlets keep better track of users and rate them based on the kind of input they have into stories.

Others, like The Guardian, are working on strategies in-house and looking at new ways to improve audience engagement.

The Guardian, with its relatively robust reader community and “Comment is free” tagline, can draw up to 65,000 comments a day. Overall, the number of comments increased 300 per cent from 2011 to 2015.

Despite an expressed commitment to its commenting culture, the site recently announced that it would limit the number of stories about race, Islam or immigration that are open to comments. Posts could be so racist and/or abusive on those subjects that moderators found it impossible to facilitate a healthy conversation.

The decision received mixed reader response, says Mary Hamilton, the Guardian’s executive audience editor, maybe because people don’t get to see the worst posts or because they misunderstood the site’s intentions.

“A lot of news organisations are turning off their comments, which isn’t something we’re doing,” she says. “We’re looking at how we can improve them. We want to see them become a genuinely useful insightful space to complement the journalism, rather than just having them disappear.”

Fiona Martin, a University of Sydney lecturer in online media, says news organisations around the world no longer have the institutional power they once did, which makes for a more open, diverse and sometimes unruly conversation about the news.

She says we have moved much of our lives into a new social space, the internet, but we are still working on some of the protocols that should dictate how we behave.

“I find that fascinating,” says Dr Martin, “because public conversations in other forums — town meetings, churches, debates — have always required rules for engagement, understandings of what appropriate argument is and some form of mediation.”

She adds: “I don’t think they existed for [website] comments early on. We’re in a catch-up phase.”

While major outlets in Australia haven’t cut their comments sections entirely, they are grappling with the same issues.

This comes at a time when reader engagement is considered imperative to cash-strapped newsrooms that need loyalty to survive.

The Age’s online editor, Michael Schlechta, says Fairfax Media recently renewed its commitment to better comment moderation.

But it’s a “work in progress”, he says.

“[P]ublic conversations in other forums — town meetings, churches, debates — have always required rules for engagement, understandings of what appropriate argument is and some form of mediation . . . I don’t think they existed for [website] comments early on. We’re in a catch-up phase.” — Fiona Martin, Sydney University lecturer

Fairfax has four moderators across its five major news sites – one based in Sydney and three in New Zealand, up from only one moderator two years ago. However, not all stories are open for comments, something Schlechta says is “simply an issue of manpower”.

The Sydney moderator says he can get through 1000 comments each day, Schlechta adds.

“The more controversial [stories] can get hundreds of comments. That [happens] pretty quickly.”

Other websites, such as Buzzfeed Australia and Guardian Australia, are part of larger international organisations with centralised moderation teams. Buzzfeed comments are moderated in New York while Guardian Australia comments are moderated in London, leaving local editors to focus on those posted on their social media pages, a space where readers often take their quarrels.

By contrast, Buzzfeed, notorious for specialising in listicles and trending stories, looks to have an easier time of it.

“The majority of stuff we publish is entertaining and fun,” says editor Simon Crerar.

When Buzzfeed does publish news stories, it closes them to comments.

“We usually feel that we’re doing a piece of reporting and we think it should stand alone,” Crerar says.

Many media organisations outsource their comment moderation to media management corporations such as Canada-based ICUC, which handles on-site comments around the clock for News Corp Australia.

Alan Oakley, News Corp’s network editorial director, says ICUC reads through hundreds of thousands of comments a month across all the media group’s mastheads. News Corp made the switch three years ago.

Oakley says the group takes a “conservative” approach to moderation. ICUC rejects about one-in-five submitted comments. But he says the group welcomes comments because stories that carry them can increase the length of time readers spend on a page.

“We’re in a battle for eyeballs,” Oakley adds. “We’re trying to get people to spend as much time with our comments as we can.”

“We’re in a battle for eyeballs. We’re trying to get people to spend as much time with our comments as we can.” — Alan Oakley, News Corp’s network editorial director

Chris Graham, the editor of left-wing New Matilda, runs a much smaller organisation, which means he is often the only person moderating comments. But he says he also receives help from readers, who will draw his attention to any problems.

“We’re quite fortunate with our readership. They understand that we’ve got bugger-all money and that we’re overwhelmed nine-tenths of the time.”

Because of his close involvement, Mr Graham says his comments section reflects his “small-L liberal” approach to comments.

“The thing I like about social media and the reason why I’m more liberal than most on the comments policy is that it’s unfiltered and that it actually is a mirror of Australian society,” Graham says. “It’s the real mirror of Australian society — warts and all.”

Graham’s progressive attitude toward comments was tested when he first took over the site in 2014, when it was bombarded by Holocaust deniers and anti-Semites.

“It kind of kept escalating,” he says. “I was approached by various members of the Jewish community who felt really strongly about New Matilda’s comments policy and allowing what we allowed.”

He made it a policy that any such comments would result in an instant ban from the site, a rule now featured in bold font on New Matilda’s FAQ page.

Graham says that while New Matilda’s comments section is mostly civil, the threat of defamation lawsuits has forced him to consider limiting access to subscribers. The reason is “purely financial”.

“We’re less likely to confront that problem if we limit those comments to people who subscribe,” he says, “because people who subscribe to New Matilda, I like to think, are more reasonable considered people.”

Unlike in the US, with its ingrained culture of free speech, Australian publications need to be mindful of potentially defamatory comments.

The Age’s Michael Schlechta says that’s another motivation behind his team’s vigilance.

“We just feel it’s an area that we need to be careful with and we want to keep it civil and productive,” he says. “And we don’t want to be sued.”

Graham says he wishes he had more time and resources to devote to comments.

“I have to be pragmatic about it,” he says. “I still have to find a way to balance that pragmatism with my belief that free and open debate is a good thing.”

For Dave Earley, Guardian Australia’s audience editor, reader interaction is just a part of the journalist’s job.

But he also acknowledges the delicate balance between moderating irrelevant, or abusive, language and encouraging healthy debate.

“It’s a balancing act in terms of: has someone done something bad enough to block them? Because we’re also not trying to just suck down debate so that only one view is presented,” he says.

Schlechta says comments submitted directly to the site are easier to deal with because they are seen by moderators before being published. But posts on Facebook pose a different challenge.

“Social media is a nightmare, to put it bluntly.”

He says one person is usually in charge of The Age’s social media feed at all times. Comments can be hidden and users can be blocked, though that doesn’t always stop them from returning to older posts.

“There’s only so much you can do,” he says. “It’s more just a challenge of being very active and making sure we watch carefully if we put controversial things up.”

Editors also avoid putting on Facebook stories about ongoing court matters, because they don’t want to be liable for any comments that might affect a trial or verdict.

At Buzzfeed Australia, where audience and social media interaction lie at the crux of its business, Crerar says they have a good sense of which articles will trigger debate.

“[Then] we make sure that our social media editor and a number of other editors, who have access to the Facebook page, are online and watching very carefully in moments where we think a particular post will prompt a debate that potentially could get out of hand. We feel like that’s kind of a duty of what we do.”

The issue gets even more fraught for certain writers, particularly women and people of colour, who can be subject to a barrage of abuse, and even threats.

Guardian columnist Jessica Valenti called for an end to online comments last September, writing that it now “feels as if comments uphold power structures instead of subverting them: sexism, racism and homophobia are the norm; threats and harassment are common.”

Simon Crerar says BuzzFeed has had to provide extra support to its LGBT reporter and Indigenous affairs reporter.

“They’re reporting on issues where sometimes people have got very strong views that don’t necessarily align with a view that most normal people would think is acceptable,” he says. “So there have definitely been incidences where we’ve worked hard to maintain control over those things.”

Former ABC moderator-cum-University of Melbourne academic Jennifer Beckett, who is researching the mental health effects of moderation, is calling for more training and better moderation tools on social media.

“Everyone now is at a point where they think commentary is important,” she says. But both readers and journalists needed to know how to interact more positively online.

Dr Martin, of Sydney University, says comments are simply “reflecting the degree of aggression in our social lives.”

“It’s just emphasised by the speed and the volume of nastiness that people see.”

She says editors and journalists themselves should have strategies in place to help them deal with that kind of reader reaction.

Nevertheless, New Matilda’s Graham thinks vibrant, even offensive, comments can be “cleansing”.

“We now have a media that does appear to be a bit more representative of our society,” he says.

“And that’s because [proprietors are] no longer able to just print a newspaper and filter the responses they get through letters to the editor. That kind of enormous power the media has wielded for generations is evaporating. I like that. I think that much power invested in any institution is a bad thing.

“I just think what we’re now seeing is the real Australia. I don’t think that’s a bad thing. I’d like to see it improve. But we’re never going to see it improve if we don’t acknowledge it for what it is.”

Dr Martin says online comment sections or Facebook feeds might be seen as negative spaces because organisations had little-to-no moderating strategies in place when they started out.

That’s why she is drafting a series of moderation principles, ones that might help Australian news publishers better incorporate engagement into their business models.

She says “participation and moderation” is just the next stage of developing journalism as a field.

“They didn’t realise the complexity of moderating debate on controversial issues. But news is all about controversial issues. It’s all about drama,” she says.