It’s late in proceedings when host Francis Leach bowls up the toughest question of the evening to Australia’s former foreign minister, Julie Bishop, before a packed auditorium in Melbourne.

He recalls her departure from the portfolio and the deputy leadership in the coup that removed Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull in August, and the decisions in the aftermath by two other female Liberal party MPs – Julia Banks and Ann Sudmalis – to quit politics at the next election because of bullying: “What’s happened to the culture of the Liberal Party where senior women, and talented women, feel that their only option is to leave?”

To this point Ms Bishop has been comfortable in front of a mostly simpatico crowd of smartly dressed young professionals and students.

She’s delivered an articulate keynote at the final 2018 event of La Trobe University’s “Bold Thinking” series, about all things big “L” Liberal – ideals, spills, leadership, women, and true to the times, conservatism. Now she sits on a panel alongside Leach, sociologist John Carroll, political expert Judith Brett, and academic journalist Andrea Carson.

She’s been largely out of the limelight in the past three months and her future plans remain unclear, though she has recently indicated she will contest the next federal election. She gave nothing more away on that front, though she wasn’t asked directly about any ambitions she might still hold.

Ms Bishop began by acknowledging how liberal democracies rose to prominence after two world wars, and how they flourished after the 1970s, before she turned to the issues they face today. She talked about public concerns regarding inequality, and how they have led to Brexit, and the election of U.S. President Donald Trump.

She reflected at length about her love for the traditional liberal ideals of her political hero, Sir Robert Menzies, especially the freedom of the individual, and borrowed this line from him about why the party took its name: “We took the name “Liberal” because we were determined to be a progressive party.”

She joked about how he might’ve reacted to the modern machinations of the Liberal party in the age of social media and digital disruption.

“Robert Menzies would have had to look up at the TV in his office and see half of his backbench giving their views on Sky News every five minutes.”

She tackled the turmoil consuming the modern party head on. “Much has been said of the so-called internal conflict between wings of the Liberal party.”

“Conservatism isn’t an ideology. Its key tenant is a skepticism of ideological approaches, and respect for institutions and traditions that are built over time … It doesn’t mean institutions are exempt from change, but that change should be incremental. Conservatism isn’t a prescriptive idea.”

John Carroll went harder when characterising the leadership challenge by Peter Dutton which deposed Malcolm Turnbull, delivered Prime Minister Scott Morrison, and has done untold damage to the party’s prospects at the looming election.

“The coup wasn’t conservative, it was insurrectionary,” he said.

“We don’t like it when a party throws out an elected Prime Minister, flouting the central idea of conservatism, but most of their reasons weren’t due to ideology. They were due to personal ambition … the usual, basic, human motives.”

He went on to draw a distinction between moral conservatism, and political conservatism. “Liberals like Abbott are moral conservatives, who don’t like pornography and euthanasia, and like good manners … ”

At the mention of Abbott’s manners, Bishop didn’t speak. Instead, she turned her head away to look pointedly into the crowd. Then, she rolled her eyes, slowly and deliberately, to the amusement of the entire room.

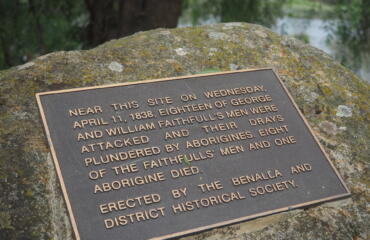

Panellists (from left to right) John Carroll, Andrea Carson, Francis Leach, Judith Brett and Julie Bishop. Photo: La Trobe University

She fired a couple of barbs at Labor about their own leadership issues, and their unwillingness to hold a bipartisan discussion on nuclear power. “I think the most recent churn of leaders clearly started with Kevin Rudd,” she said.

“They just didn’t like Kevin. That’s not reason to get rid of a leader. But that then set the benchmark … And then we saw it in our own party.”

“It’s rather ironic that Kevin Rudd should bequeath to Bill Shorten a mechanism to keep him in office,” she said, bringing up the changes in Labor party rules in 2013 that make it more difficult, though not impossible, to knife a leader. Shorten was instrumental in the removal of Rudd, and Julia Gillard, from the Prime Ministership during Labor’s own spills.

Bishop refused to be drawn into whether or not she’s in favour of similar rules for her own party, but said they wouldn’t be feasible because of traditional Liberal ideals.

“I don’t see the Liberal party members ever giving up the right to elect, and un-elect, the leader of the party … I don’t envisage it, whether I liked it or not. You can’t envisage a circumstance where Liberals would give up their right, that they so jealously guard.”

In her keynote, she expressed not just her belief in the power of women, but her belief that equal representation is crucial for Australia to reach its potential. “No nation will reach its full potential unless it fully engages with and harnesses the skills, talents, ideas and energy of the 50% of its population that is female – in our case, the 51%,” she said.

That, the standout line of her script, seems somewhat at odds with the way she now answers Leach on the party’s treatment of women, and what the resignations of Banks and Sudmalis might signal.

“Well, that’s a distressing situation in any workplace and I’m doing something about it. I’m supporting an initiative in Western Australia called Empowering Women, where the former state president of the Liberal party, Danielle Blaine, and I, as patron, are contacting young professional women, and asking them to come along to Liberal party functions, not to join the Liberal party, but just to come along and listen to the debate,” she says.

“Tonight in Perth they’re launching Empowering Women, and they have 65 young women who have never been involved in politics attending an event to hear more.”

“You can talk all you like about quotas and targets. You need a pool of talented women who are prepared to be considered for politics. Otherwise you are just going and choosing a woman and saying, ‘please come in, we need to make up a quota’,” she says.

Leach tries again: “You had a number of those [talented women], and they decided they’re going to walk away.”

The answer is that of the veteran diplomat. “Well, people leave politics for all sorts of reason. We’ve also got male members who are leaving politics. Everyone has a different reason for saying they’ve had enough and want to move on.”