Death is not always sudden. Most of us will die slowly, not always peacefully, in an uneven series of ups and downs until it’s over.

“Almost everyone who isn’t really unlucky gets to 80,” says Charlie Corke, an intensive care specialist at Barwon Health’s University Hospital Geelong. Indeed, two-thirds of Australians will die after age 75, of chronic illnesses such as coronary heart disease, dementia and lung cancer.

“But the time between 80 and 90 is bumpy,” he adds. “And not that many people get to 90.”

Despite the inevitability of death, most people do not speak to their health professionals about how they want to die. And Dr Corke says it can be counterintuitive for doctors, who have been trained to save life at all costs.

They might also be reluctant to bring it up; after all, it’s hard telling someone they are dying.

“We’re looking at somebody who’s got about a year to live. That last year is about how bumpy you make it, how much you fight, how much acceptance there is. And that’s a very new concept, certainly for doctors.” — Dr Charlie Corke

This lack of willingness to start the conversation about dying is a big problem, according to Dr Corke, an active voice on end-of-life issues. He also starred in a 2010 episode of the ABC series Compass, which dealt with life support for the elderly.

Dr Corke believes many patients spend the last days, months and years of their lives in and out of hospital, undergoing invasive treatments though there is no hope for a cure. This isn’t necessarily best for them or their families.

After discovering that many terminally ill patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) had not had this discussion, Barwon Health decided its doctors needed a little practice.

It designed a two-day training course called iValidate, which gives doctors the chance to work on their skills with actors.

David Carman, five years out of medical school, took the course earlier this year, practising his version of the talk with an actor pretending to have lung cancer and mobility issues.

Dr Carman asked the actor about his life, what he wanted to do with the time he had left, what sort of medical interventions he would want if he came to the hospital in the future.

“I suppose one of the more important skills is, sort of, listening. Giving him the time to air his thoughts and his grievances,” says Dr Carman. “And I guess getting him to a place where he feels like he can discuss those with you even though it’s something he might not be comfortable with discussing with anyone.”

The trick is to identify patients who have a finite amount of time left, and to talk to them before their condition gets much worse and other people have to make decisions for them.

“We’re looking at somebody who’s got about a year to live,” says Dr Corke. “Because that last year is about how bumpy you make it, how much you fight, how much acceptance there is.

“And that’s a very new concept, certainly for doctors.”

But there is growing awareness within the medical community — and even the public — that we need to re-examine the way we deal with death. And government has taken notice.

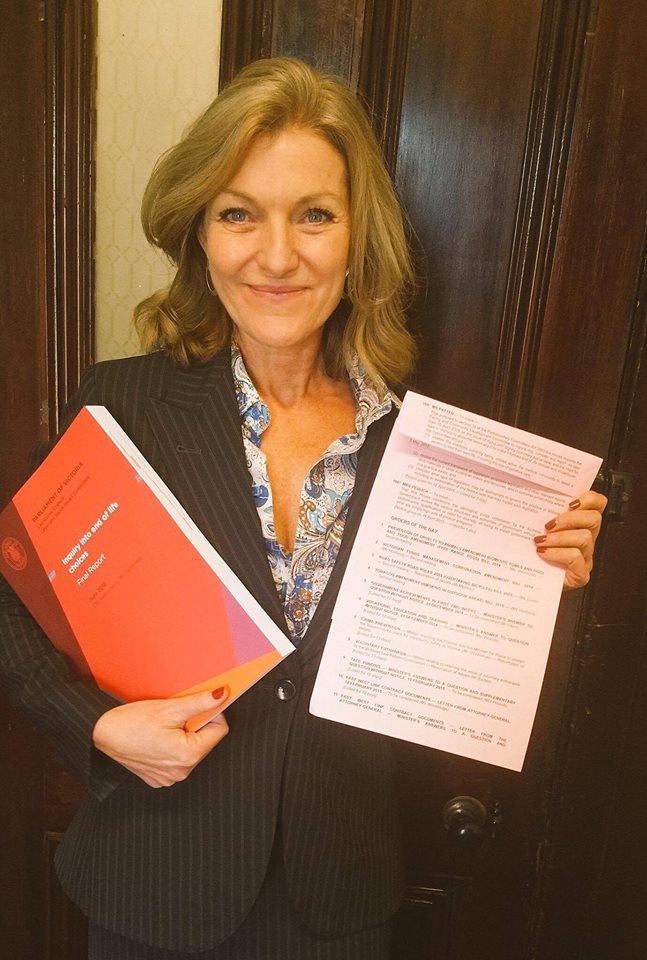

A Victorian parliamentary inquiry report released in June recommended a number of reforms to the medical system’s approach to end-of-life care, including a framework for legalising assisted dying.

Victorian MP Fiona Patten, who initiated the inquiry, says the public debate over voluntary euthanasia, while important, overshadows a much-needed larger discussion about dying.

“Making that decision at end-of-life is one thing. But the conversation about getting to that point is equally and probably more important,” she says.

Though a large majority of the 1000 public submissions to the inquiry addressed assisted dying, Ms Patten says most of the report takes a broader look at Victoria’s end-of-life “toolbox”.

Those options sit on a spectrum from intensive care, which focuses on life-sustaining treatment, to palliative care, which stresses overall wellbeing and pain management.

But the committee also heard that doctors often avoided starting discussions about palliative care — or dying in general. They felt pressure from patients and their families to be positive, to keep trying, even when they knew someone was dying.

“The number of times that we heard doctors say that sometimes it’s easier to treat than have the conversation . . . ” says Ms Patten.

As a result, dying in Australia is “more institutionalised than the rest of the world”, according to a 2014 Grattan Institute report, which found that 70 per cent of Australians would prefer to die at home but only 14 per cent do. Without a plan for how they would like to die, many people can experience lonely, stressful or impersonal deaths in acute care units, where the goal is to cure.

Melissa Bloomer, a Deakin University lecturer and former ICU nurse, says too many terminally ill people die in hospital when they don’t have to.

“Too often, I saw patients who were kept alive in intensive care units supported by a whole lot of machinery simply because families hadn’t come to terms with the fact that death was the outcome,” she says.

Dr Bloomer’s own research found that families needed up to 22 conversations with medical staff to fully understand what was happening.

Deakin University lecturer Sharyn Milnes, who co-ordinates ethics and communications training for medical students, says lack of understanding is a “big problem”.

“A lot of people don’t even know they’re dying,” she says. “They come into hospital and have this one little problem fixed, sent to rehab or sent to a nursing home and nobody’s even said to them, ‘the most you’ve got to live is 12 months’.”

Many practitioners believe earlier references to palliative care or other underused resources, such as advance care planning, only benefits patients. They can make choices about how they want to spend the rest of their life — before it’s too late.

But advanced care directives, special plans that detail a patient’s medical wishes in the event of an emergency, are relatively rare. Less than 1 per cent of Australians over 70 have one.

Ms Patten says her own mother’s final days were unnecessarily turbulent. Her mother was airlifted from Canberra to Wagga Wagga for radiology, accidentally dropped on the tarmac during the delayed trip and was later deemed too sick for the treatment.

Death in Australia

► 66% of people die after the age of 75

► About 85% of people die of a chronic disease

► About 70% of deaths are expected

► Though 70% of people want to die at home, only 14% do

► 54% of people die in hospitals; 32% of people die in residential homes

Sources:Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; Grattan Institute; End of Life Choices inquiry report

“Had I known then what I know now, I would have had a different conversation with the doctor,” Ms Patten says. “Not that I actually did get the conversation with the doctor . . . I understand that he was just thinking ‘well, maybe we can do this’.

“She was only in her 60s,” Ms Patten says of her mother. “You want to try and do something. But, again, that showed that lack of confidence the doctor had in having that conversation.”

Many health practitioners and palliative care workers believe both doctors and patients are hesitant to consider palliative care because it feels like giving up, says Ranjana Srivastava, an oncologist and health columnist, who spoke to the inquiry.

“They are difficult conversations to have,” Dr Srivastava told The Citizen. “It’s always nicer and more tempting for a doctor to say, ‘let’s try something else’, rather than have a conversation about ‘maybe we’re not winning here’.”

The urge to continue treatment is especially strong when children are involved. Beau Thompson, a clinical nurse specialist at Melbourne’s Royal Children’s Hospital, says “people are a lot more thorough at making sure that they’ve tried everything. Even though that everything may be the slimmest of slim chances.”

“I find it frustrating from that point, that we may overtreat people and then limit the actual amount of quality time the patient may actually have with family and loved ones.”

Mr Thompson, who is working on helping his team develop better communication practices regarding withdrawal of care, says more communications training for medical staff would result in better emotional outcomes for patients.

“There comes a time where no matter what you do isn’t going to change anything for the patient,” he says. “And then it comes down to what is best for the patient and their family. Is quality better over quantity? Or is quantity more important than quality? Nine times out of 10 they’ll say quality.”

The inquiry’s report stressed the need for more programs that teach practitioners how to talk to patients about their end-of-life options, including regular training for clinical staff.

Right now, formal training programs are few and far between, according to Dr Corke, who says several other hospitals have expressed interest in the iValidate program.

But the lack of knowledge about palliative care starts in medical school.

“Most doctors will never deliver a baby but every doctor is taught how to deliver a baby,” says Ms Patten. “Almost all doctors will have a patient that becomes terminally ill. But we don’t teach them how to talk about that.”

Deakin University asks medical students to complete virtual simulation programs, which take students through potential conversations with dying patients and their families — a sort of “choose your own adventure” for end-of-life choices. The inquiry’s report called on the Victorian Government to make such programs a part of medical courses across the state.

This would help combat the well-documented phenomenon known as the “hidden curriculum”, in which junior doctors often mimic the bad habits of older practitioners.

Ashley Garnett, an intensive care registrar at University Hospital Geelong, also took the iValidate course last year. Before that, his earliest memories of talking to patients about end-of-life choices were when he saw his senior doctors doing it.

He saw one doctor at a previous hospital approach a man who didn’t know he was dying and say: “We can’t fix you and you’re going to die.”

“Then he walked away. That was it. That was the extent of the discussion. It was horrific,” he adds.

Dr Garnett says iValidate gave him a framework to discuss end-of-life options in a more efficient way, rather than just dancing around the issue until getting to the point.

The Victorian Government has until December to respond to the inquiry. But half of the ministers in Premier Daniel Andrews’ cabinet have said they support voluntary euthanasia — most notably, Health Minister Jill Hennessy.

Mr Andrews, though he has not declared support for assisted dying, has admitted the state is not living up to the expectations of the dying.

“If you search your conscience, and you search your own personal experience, I think more and more Victorians are coming to the conclusion that we are not giving a dignified end, we are not giving the support, the love and care that every Victorian should be entitled to in their final moments,” Mr Andrews said.

In July, shortly after the release of the inquiry’s final report, the Government outlined a set of policy priorities for end-of-life care, committing an immediate $7.2 million to expand the palliative care sector. Additionally, a bill introduced into state parliament last month would allow Victorians to make decisions about their end-of-life carethat are legally binding, making it much easier for doctors to know what a patient would want.

Understandably, however, talking about death is no one’s idea of a good time. Dr Srivastava says Australians exist in a culture that is “death-denying”. We don’t want to talk about it.

A number of organisations have developed resources to get people started. Death Over Dinner helps individuals plan dinner parties where death is discussed. The Groundswell Project organises Dying to Know Day each August 8. Palliative Care Australia has a Dying to Talk discussion starter pack.

But Dr Corke says planning for death is not for everyone.

“Different people have very different amounts they want to invest in it,” he says. The most important thing is for doctors to start asking: “Tell me what matters to you. Tell me what is unacceptable to you. Let’s have a chat about it,” he says.

► An edited version of this story also appears at The Monthly.