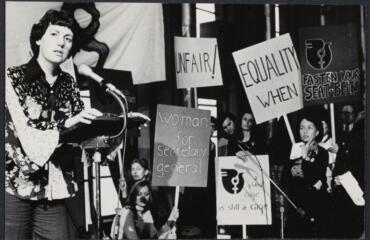

Ruth Williams would be the first to tell you she’s not an ideal companion for a relaxing stroll.

“Don’t ever go for a walk with me now, because every time I see rubbish I think ‘that’s going to go into the creek’,” she says. The urge to stop and retrieve it inevitably wins.

Williams is a coordinator of the Darebin Creek Sweepers, a community volunteer group dedicated to protecting the creek from plastic pollution. Since she joined the group, Williams says she’s become hyper-aware of its toll on the environment.

The Darebin Creek runs for more than 50 kilometres from the rural community of Woodstock and down through the Darebin Parklands before finally pouring into the Yarra river.

It is home to more than 100 bird species, 20 varieties of reptiles and another 10 of amphibians. From kangaroos in the northern rural areas to flying foxes near the Yarra River, Darebin Creek hosts a diverse ecosystem, much of within otherwise urban, developed neighbourhoods.

But it also hosts infinite varieties of plastic, and it’s everywhere – through the bends in the stream, trapped between the rocks, caught in the long grass.

Williams says the most common type of waste is plastic – mostly bottle caps. Other types of waste includes syringes, beer bottles and single-use plastic bags.

“People come here and party, and do all sorts of stuff, I have picked so many syringes along the creek,” says Williams.

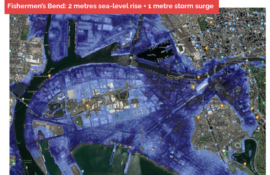

A Google Earth image showing the urbanisation around Darebin Creek.

Increased community engagement, including the efforts of volunteers like Williams to clean up the environment, is one of the ambitions laid out by the Darebin City Council Water Management Strategy.

The plan, launched in 2015, also aims to create healthy waterways, ecosystems and good urban design according to priorities laid out until 2025.

As well as being a habitat for a number of native species, the creek and surrounding parklands already play a significant role in the lives of the local community.

A report by Parks Victoria in 2015 found that access to “high quality” parks created positive social outcomes for the surrounding community, including improved social cohesion, mental and physical health.

However, the report also found these positive health outcomes could be diminished by a number of factors – including pollution.

The open dog park is particularly important to one local resident – Rain, an eight-month-old Australian cattle dog. Belinda Donaldson, Rain’s owner, says the Darebin dog park is the best in the area due to its natural terrain and wide open spaces.

The day The Citizen visits, we meet Heidi Newlan, a family daycare educator who has brought two children to the parklands to play in the natural surroundings. Newlan says access to expansive natural habitat within the city is crucial for children. As well as the obvious benefits of fresh air and exercise, she says it also encourages them to use their imagination for play.

She always picks up rubbish when she visits the park, and encourages the children to do so, too, so long as the litter is safe for them to handle.

Peter Grenfell has been an education officer at Darebin Creek for more than 10 years, working to protect the creek through raising awareness.

Grenfell runs monthly water quality check ups, which include reporting the presence of aquatic macroinvertebrate fauna, an indication of good water quality.

He says that the creek used to run low in the dry hot season, but that now it runs all year, due to some creeks being redirected and with increased runoff.

Grenfell says the source of the pollutants impacting the creek can be hard to nail down, as it runs through urban, industrial areas where pollutants might escape, knowingly or unknowingly.

The urbanisation of the surrounding area also contributes to the creek’s pollution – plastic litter, being the most visible. But less obvious pollutants – detergents and other chemicals – are also doing damage, he says, and are commonly found washing into the creek from surrounding roads.

Grenfell recalls a particularly nasty pollution incident in 2017 when someone dumped some insect killer into the drains, killing fish and eels through a substantial stretch of the river. Events like this could be prevented with education, he says. “I doubt they knew what they were doing.”

With stormwater not being filtered at any point before entering the stream, Grenfell wants the community to remember a simple catchphrase: the only thing that should go down the stormwater drains is rain water.

Protecting Darebin Creek from pollution may seem like an uphill battle to some. However, according to David Gifford – another Darebin Creek Sweepers organiser – the community effort to clean up the creek is only growing.

“We have some regular volunteers who join us but we also have a lot of new people who want to come help whenever they have time,” Gifford says.

To visit this multi-media report and other stories in our series ‘The Creeks of Melbourne’, click here.